Introduction

When India became independent in 1947, the economy of the country was very fragile and facing many problems. The level of poverty was very high. Nearly 80% of the population was living in rural areas, depending on agriculture for their livelihood. As the craft-based occupations had suffered during British rule, many skilled artisans had lost their livelihood. As a result, agriculture was overcrowded, and the per capita income from agriculture was very low. Agriculture was also characterised by semi-feudal relations between landowners and cultivators or peasants, who were often exploited by the land-owning classes.

The industrial sector had grown in the decades before Independence, but it was still quite small. The best known heavy industry was Tata Iron and Steel. Besides this, the main manufactures were cotton spinning and weaving, paper, chemicals, sugar, jute and cement. Engineering units produced machinery for these units. However, the sector was relatively small and did not offer a significant potential for employing the surplus labour from the agricultural sector. In fact, the industry sector only accounted for 13% of the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 1950. Most manufactured consumer goods were imported. The Indian offices of major foreign companies were involved only in marketing and sales, and not in manufacturing.

Thus, the new government of India was faced with the mammoth task of developing the economy, improving conditions in agriculture, widening the manufacturing sector, increasing employment and reducing poverty.

Socialistic Pattern of Society

Economic development can be achieved in many ways. One option would be to follow the free enterprise, capitalist path; the other was to follow the socialist path. India chose the latter. In fact, the Preamble to the Indian Constitution, cited in the previous lesson, stated unambiguously that India would be “a sovereign, socialist, secular democratic republic”. The objectives of this socialist pattern of development were: the reduction of inequalities, elimination of exploitation, and prevention of concentration of wealth. Social justice meant that all citizens would have an equal opportunity to education and employment. This essentially entailed the active participation of the state in the process of development.

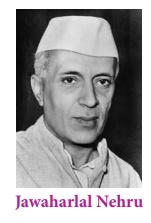

In agriculture, social and economic justice was to be achieved through a process of land reforms which would empower the cultivator. In industry, the state would play an active role by setting up major industries under the public sector. These were to be achieved through a comprehensive process of planning under Five Year Plans. These strategies had been borrowed from the Soviet experience of rapid economic development. Nehru was a great admirer of the success of the Soviet Union in achieving rapid development, and thus the ideology on which this strategy is based is often referred to as “Nehruvian Socialism”.

Agricultural Policy

At the time of Independence, agriculture in India was beset with many problems. In general, productivity was low. The total production of food grains was not enough to feed the country, so that a large quantity of food grains had to be imported. Nearly 80 percent of the population depended on agriculture for their livelihood. This automatically reduced the income of each person to very low levels. This is a situation described as ‘disguised unemployment’. That is, even if many people shifted to other occupations, total production levels would remain the same, because this surplus population was not really required to sustain the activity, and was, in effect, unemployed. Given the high level of poverty among the rural population, most of them were heavily indebted to moneylenders.

The backwardness of agriculture could be attributed to two factors: institutional and technological. Institutional factors refer to the social and economic relations that prevailed, particularly between the land-owning classes and the cultivating classes. Technological factors relate to use of better seeds, improved methods of cultivation, use of chemical fertilizers, use of machinery like tractors and harvester combines, and provision of irrigation. The government decided to tackle the institutional drawbacks first and began a programme of land reforms to improve the conditions in agriculture. The basic assumption was that such measures would improve the efficiency of land use or productivity, apart from empowering the peasants by creating a socially just system.

Land Reforms and Rural Reconstruction

Under the Constitution of India, agriculture was a ‘state subject’, that is, each state had to pass laws relating to land reforms individually. Thus, while the basic form of land reforms was common among all the states, there was no uniformity in the specific terms of land reform legislation among the states.

Three systems of revenue collection had been introduced by the British. In Bengal and most of north India, the Permanent Settlement placed the responsibility of paying land revenue on the rentier class of zamindars. In south India, the cultivators paid the land revenue demand directly to the government under the system known as ‘ryotwari’ (‘ryot’ means cultivator). The third system, found in very small pockets of the country, was ‘mahalwari’ where the village was collectively responsible for paying the land revenue.

(a) Zamindari Abolition

Abolition of Zamindari was part of the manifesto of the Indian National Congress party even before Independence.

What was Zamindari and who were the zamindars?

Zamindar referred to the class of landowners who had been designated during British rule as the intermediaries who paid the land revenue to the government under a Permanent Settlement. They collected rent from peasants cultivating their land and were obliged to remit a fixed amount to the government as land taxes. There was no legal limit to these demands, and zamindars generally extorted high rents from the cultivators leaving them impoverished. In public opinion, these zamindars were considered to be a decadent, extravagant and unproductive class who were living on unearned income. Abolishing their privileges and restoring land to the cultivators was therefore a prime objective of the government.

Most provinces in India had enacted laws abolishing the zamindari system even before the Constitution was framed. By 1949, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Madras, Assam and Bombay had introduced such legislation. West Bengal, where the Permanent Settlement was first introduced, the act was passed only in 1955. Land taken away from the zamindars was distributed among the tenants. The provincial legislatures also recommended the amount of compensation to be paid to the zamindars.

Zamindars in various parts of the country challenged the constitutionality of the zamindari abolition laws in court. The government then passed two amendments to the Constitution, the First Amendment in 1951 and the Fourth Amendment in 1955, which pre-empted the right of zamindars to question the takeover of their land or the value of the compensation.

Finally, zamindari abolition was completed by 1956, and was possibly the most successful of the land reforms. About 30 lakh tenants and sharecroppers gained ownership of 62 lakh hectares of land. The total compensation actually paid to the zamindars amounted to ₹ 16,420 lakhs (which amounted to only about one-fourth of the total compensation amount due).

In sum, however, the reform only achieved a very small part of the original objective. Many zamindars were able to evict their tenants and take over their land claiming that this land was under their ‘personal cultivation’. Thus, while the institution of zamindari was dismantled, many landowners continued in possession of vast tracts of land.

(b) Tenancy Reform

Nearly half of the total cultivated land in India was under tenancy. Tenancy refers to an arrangement under which land was taken on lease from landowners by cultivators under specific terms. Not all tenants were landless peasants. Many small landowners who wanted to cultivate additional land leased out land from other landowners. Some richer landowners also took additional land for cultivation on lease. In general, the rent was paid in kind, as a share of the produce from the land. It was common for large landowners to lease out the land to tenants. Usually these tenancy arrangements continued for long periods of time. The rents received by the landowners generally amounted to about 50% or more of the produce from the land, which was very high. Tenancy was a customary practice and agreements were rarely recorded. Thus, tenants of long-standing were almost never deprived of tenancy rights. However, tenants could also be evicted at short notice, and tenants therefore always lived under some uncertainty.

Tenancy reform was undertaken with two objectives. One was to empower the cultivators by protecting them against the landowners. The other was to improve the efficiency of land use, based on the assumption that tenancy was inefficient. Landowners rarely had any incentive to invest in improving the land, and were interested only in deriving an income from their land. Tenants, who had no ownership rights and were liable to pay high rents, had neither the incentive nor surplus money to invest in land.

Tenancy reform legislation was aimed at achieving three ends:

(i) to regulate the rent;

(ii) to secure the rights of the tenant;

(iii) to confer ownership rights on the tenants by expropriating the land of the land owners.

Legislation was passed in the states regulating the rent at one-fourth to one-third of the produce. But this could never be implemented successfully. The agricultural sector had a surplus of labour whereas land was a resource in short supply. Price controls did not work in a situation when the demand exceeded the supply. All that happened was that rent rates were pushed under the table without any official record.

Laws to secure the rights of the tenant and to make tenancy heritable were equally unsuccessful. Tenancy agreements were made orally, and were unrecorded. The tenant thus always had to live with the uncertainty that their land could be resumed by the landlord any time.

When tenancy reform laws were announced many landowners claimed to have taken back their land for ‘personal cultivation’ and that tenants were only being employed as labour to work the land. Tenancy reform was bound to be ineffectual in the absence of a comprehensive and enforceable land ceiling programme.

Land reform measures initiated in Kerala and West Bengal met with reasonable success. While abolition of landlordism was remarkably successful, conferment of ownership rights to tenants had mixed results.

(c) Land Ceiling

Land ceiling refers to the maximum amount of land that could be legally owned by individuals. Laws were passed after the 1950s to enforce it. In Tamilnadu it was implemented first in 1961. Until 1972, there was a ceiling on the extent of land that a ‘landholder’ could own. After 1972, the unit was changed to a ‘family’. This meant that the landowners could claim that each member of the family owned a part of the land which would be much less than the prescribed limit under the ceiling.

Deciding the extent of land under land ceiling was a complex exercise, since land was not of uniform quality. Distinctions had to be made between irrigated and unirrigated dry land, and single crop and double crop producing land. At the same time, exemptions from the Act were granted to certain categories of land such as orchards, horticultural land, grazing land, land belonging to religious and charitable trusts, and sugarcane plantations. These exemptions were also used to evade the land cieling acts and reported cases of manipulation of land records adversely impacted the otherwise laudable initiative.

Ultimately, only about 65 lakh hectares of land was taken over as surplus land. This was distributed to about 55 lakh tenants–an average of a little over 1 hectare per tenant. Clearly, with their political power the dominant castes who were the big landowners managed to dilute and vitiate the entire legislation.

Efforts like Bhoodan started by Vinoba Bhave to persuade large landowners to surrender their surplus land voluntarily attracted much public attention.

(d) Overall Appraisal

Land reform legislation has overall not been a great success. In economic terms, the dream of an agricultural sector prospering under peasant cultivators with secure ownership rights has remained just that – a dream – and there was no visible improvement in efficiency. In more recent years, when agriculture has grown due to technological progress, a more efficient land market is seen to be operating which is more conducive for long term growth.

In terms of social justice, the abolition of the semi-feudal system of zamindari has been effective. The land reform measures have also made the peasants more politically aware of their rights and empowered them.

Development of Agriculture

(a) Green Revolution

By the middle of the 1960s the scenario with regard to food production was very grim. The country was incurring enormous expenditure on importing food. Land reforms had made no impact on agricultural production. The government therefore turned to technological alternatives to develop agriculture. High Yielding Variety (HYV) of seeds of wheat and rice was adopted in 1965 in select areas well endowed with irrigation.

Unlike traditional agriculture, cultivation of HYV seeds required a lot of water and use of tractors, chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The success of the initial experimental projects led to the large-scale adoption of HYV seeds across the country. This is generally referred to as the Green Revolution. This also created an enormous demand for chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and these industries grew as well.

Finally, within twenty years, India achieved self-sufficiency in food production. Total rice production increased from 35 million tonnes in 1960–61 to 104 million tonnes in 2011–12. The increase in wheat production was even more impressive, from 11 million tonnes to 94 million tonnes during the same period. Productivity also increased. A large reserve stock of food grain was built up by the government through buying the surplus food grain from the farmers and storing this in warehouses of the Food Corporation of India (FCI). The stored food grains were made available under the Public Distribution System (PDS) and to ensure food security for the people.

Another positive feature has been the sustained increase in the production of milk and eggs. Due to this, the food basket of all income groups became more diversified.

While the Green Revolution has been very successful in terms of increasing food production in India, it has also had some negative outcomes. First of all, it increased the disparities between the well-endowed and the less well-endowed regions. Over the decades, there has been a tendency among farmers to use chemical fertilizers and pesticides in excessive quantities resulting in environmental problems. There is now a move to go back to organic farming in many parts of the country. The lesson to be learnt is that development comes at a certain cost.

(b) Rural Development Programmes

By the 1970s, the levels of poverty had not declined in spite of overall development of industry and agriculture. The assumption that development would solve the problem of poverty was not realised, and nearly half the population was found to be living below the poverty line. (The poverty line is defined as the level of expenditure required to purchase food grains to supply the recommended calorie level to sustain a person.) Though the percentage of the persons below the poverty line did not increase, as the population grew, the number of persons living below the poverty line kept increasing.

Poverty prevailed both in rural and urban areas. But since nearly three-fourths of the population lived in rural areas, rural poverty was a much more critical problem requiring immediate attention. Poverty levels were also much higher among specific social groups such as small and marginal farmers, landless labourers and depressed classes in resource poor regions without irrigation and with poor soil, etc.

A whole range of rural development programmes was introduced by the government to tackle rural poverty. These included Community Development Programmes, reviving local institutions like Panchayati Raj, and targeted programmes aimed at specific groups such as small and marginal farmers. The thrust was on providing additional sources of income to the rural households to augment their earnings from agriculture. Two major programmes are explained in greater detail below.

Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP), 1980–1999

In 1980 a consolidated rural development programme called Integrated Rural Development Programme was introduced. The purpose was to provide rural households with assets which would improve their economic position, so that they would be able to come out of poverty. These could be improvements to the land, supply of cows or goats for dairying or help to set up small shops or other trade-related businesses. Introduced in all the 5011 blocks in the country, the target was to provide assistance to 600 families in each block over five years (1980–1985), which would reach a total of 15 million families.

The capital cost of the assets provided was covered by subsidies (divided equally between the Centre and the States) and loans. The subsidy varied according to the economic situation of the family receiving assistance. For small farmers, the subsidy component was 25%, 33.3% for marginal farmers and agricultural labourers, and 50% for tribal households. Banks were to give loans to the selected households to cover the balance of the cost of the asset. About 53.5 million households were covered under the programme till 1999.

Dairy animals accounted for 50% of the assets, non-farm activities for 25% and minor irrigation works for about 15%. The functioning and the effects of IRDP were assessed by many economists as well as government bodies. These studies raised many questions about the end result.

Lack of proper selection procedures for identification of beneficiaries, insufficient investment per household, absence of post implementation audits of the scheme, regional disparities in lifting the identified beneficiaries above the poverty line was a major issue.

Considering the limited success achieved by the programme it was restructured in 1999 as a programme to promote self-employment of the rural poor.

Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 (MGNREGA)

Over the years, due to concerted efforts, the percentage of households below the poverty line has come down substantially in India. It is now widely recognised that eradicating rural poverty can be achieved only by expanding the scope for non-agricultural employment. Many programmes to generate additional employment had been introduced over the years. Many were merged with the employment guarantee scheme, which is now the biggest programme on this front in the country.

The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (subsequently renamed MGNREGA after Mahatma Gandhi) was passed in 2005, with the aim of providing livelihood security to poor rural households. This was to be achieved by giving at least 100 days of wage employment each year to adult members of every household willing to do unskilled manual work. This would provide a cushion to poor rural households which could not get any work in the lean agricultural season which lasted for about three months each year. In this exercise, the work undertaken would create durable assets in rural areas like roads, canals, minor irrigation works and restoration of traditional water bodies.

The earlier targeted programmes of rural development were based on the identification of below poverty line families, which had led to several complaints that ineligible families had been selected. MGNREGA, however, is applicable to all rural households. The reasoning is that it is a self-targeting scheme, because persons with education or from more affluent backgrounds would not come forward to do manual work at minimum wages.

The earlier employment generation programmes did not give the rural poor any right to demand and get work. The significant feature of this Act is that they have the legal right to demand work. The programme is implemented by Gram Panchayats. The applicants have to apply for this work and are provided with job cards. Work is to be provided by the local authorities within 15 days. If not, the applicant is entitled to an unemployment allowance. The work site should be located within five kilometres of the house of the applicant.

No contractors are to be involved. This is to avoid the profits which will be taken by the middlemen thus cutting into the wages. The ratio of wages to capital investment should be 60:40. One-third of the workers would be women. Men and women would be paid the same wage.

As with all government programmes, many studies have brought out the weaknesses in the implementation of MGNREGA. On the positive side, agricultural wages have gone up due to the improved bargaining power of labour. This has also reduced the migration of agricultural workers to urban areas during the lean period or during droughts. One of the most important benefits is that women are participating in the works in large numbers and have been empowered by the programme.

Wages of the workers are paid directly into bank accounts or post office accounts to ensure transparency and hassle – free transfer of payments. The involvement of civil society organisations, non-governmental organisations and political representatives, and a more responsive attitude of the civil servants have improved the functioning of MGNREGA in states like Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan. Efficiency has increased up to 97%.

Between 2006 and 2012, around ₹ 1,10, 000 crores had been distributed directly as wage payment under the programme, generating 1200 crore person-days of employment. In spite of many shortcomings, the functioning of the programme has improved due to higher levels of consciousness among the rural poor and concerned civil society organisations. Though many critics feel that the high expenditure involved in the programme increases the fiscal deficit, the programme remains popular and nearly one-fourth of all rural households participate in the programme each year.

Development of Industry

India was committed to the idea of promoting rapid industrial growth for economic development. Development can be achieved through several pathways. In a country like India with a large population where many raw materials were grown or were available, processing industries which were more labour-intensive would have also led to industrial growth. Alternatively, the Gandhian model stressed a model of growth with village and cottage industries as the ideal way to produce consumer goods, which would eliminate rural poverty and unemployment.

But the government adopted the Nehruvian model of focusing on large scale, heavy industry to promote wide-ranging industrial development. In keeping with the basic principle of a “socialistic society”, the state would play a major role in developing the industrial sector through setting up units wholly owned by the state. The emphasis on heavy industry was to promote the production of steel and intermediate products like machines, chemicals and fertilizers for the developing industries. The social purpose that would be achieved by this model of development was to restrict private capital which was considered to be exploitative and excessively profit-oriented, which benefited a small class of capitalists

(a) Industrial Policy

A series of Industrial Policy statements were adopted to promote these objectives. The first policy statement was made in 1948. It classified industries into four categories:

1. Strategic industries which would be state monopolies (atomic energy, railways, arms and ammunition);

2. 18 industries of national importance under government control (heavy machinery, fertilizer, heavy chemicals, defence equipment, etc.);

3. Industries in both the public and private sectors;

4. Industries in the private sector.

The most definitive policy statement was the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956 which classified industries into three categories: Schedule A industries were under the monopoly of the state; Schedule B industries, the state could start new units but the private sector could also set up or expand their units; Schedule C were the remaining industries.

The Industrial Development and Regulation Act of 1951 was an important instrument for controlling the private sector. This Act stipulated that no new industrial units could be set up, nor the capacity of existing units expanded without a licence or permit from the government.

The Policy Statement of 1973 encouraged large industrial houses to start operations in rural and backward areas to reduce regional imbalances in development. The Policy Statement of 1977 was framed by the short-lived Janata government which was aimed at promoting rural, village and small scale industries.

The Policy Statement of 1980 was announced by the Congress government which also aimed at promoting balanced growth. Otherwise all these statements continued the ideology of a strong public sector owned by the state and control over the private sector and especially the large business houses.

There were also other interventions which intruded into the market economy. For instance, inputs produced in the private sector like cement were rationed, and permits had to be obtained even for private construction of houses. The manufacture of consumer goods was severely restricted under the licensing policy. This was partly an expression of the ideology of reducing inequalities in consumption between the affluent and weaker sections of society. But it was also a way to ensure that scarce resources like steel, cement etc. would be used in strategic industries for the long-term development of the economy.

Many important industries and services were nationalised. These included coal mines, petroleum companies, banking and insurance services. Private entrants have been allowed into some of these activities only in recent years.

(b) Public Sector

There were only five public sector enterprises in India in 1951. By 2012, this number had increased to 225. The capital investment increased from ₹ 29 crores in 1951 to 7.3 lakh crores in 2012. The setting up of public sector enterprises in heavy industry was again dictated by two considerations. First, at the ideological level, the government was committed to a socialistic pattern of development which involved a high degree of state control over the economy. But at a more practical level, the government had to take over the responsibility for the establishment of heavy industrial units which required a very high level of investment. These were known as “long gestation” projects, that is, it would take many years before such units would be able to start production.

In the 1950s, the private sector did not have the resources or the willingness to enter into such investment. Steel plants in Bhilai (Chhattisgarh), Rourkela (Odisha), Durgapur (West Bengal), Bokaro (Jharkhand), engineering plants like Bharat Heavy Electricals (BHEL) and Hindustan Machine Tools were all set up in the 1950s in collaboration with Britain, Germany and Russia which provided the technical support.

Units which did not have to be located near raw material sources were set up in backward areas to reduce regional disparities in industrial and economic development. BHEL was first set up in Bhopal, and later in Tiruchirappalli, Hyderabad and Haridwar. Steel plants were set up in the relatively backward belt of Orissa, Bihar and West Bengal. Public sector enterprises also contributed to the national exchequer because their profits accrued in part to the central government. Thus the growth of the public sector served many economic and social purposes, in addition to creating industrial capacity in the country.

(C) Crisis in Public Sector Industrial Units

By 1991 it was clear that public sector enterprises were facing severe problems. While on the whole they were showing a profit, nearly half of the profit was contributed by the petroleum units. Many were making continuous losses. Part of the problem lay in the expansion of the public sector into non-strategic areas like tourism, hotels, consumer goods (for instance, in the 1970s, television sets were produced only by public sector companies) and so on.

There were many factors which contributed to the poor performance of public sector enterprises. Decisions on location were made for political rather than efficiency considerations. Delays in construction resulted in cost overrun, so that the units were overcapitalized. Administrative prices were not always economical and did not make sense when the intermediate goods produced in the public sector were used as inputs in the private sector. Public sector units were also overstaffed, though the technology of heavy industries did not require so many workers. This increased the operating cost of the units. Bureaucrats were entrusted with the management of public enterprises, leading to inefficiency in management. Recognising all these problems, the government began a programme of disinvestment of the loss-making and non-strategic units in 1991.

In spite of all the shortcomings, the strategy of industrialisation by concentrating on building up long-term industrial capacity through the establishment of heavy industries has been successful in making India into a modern, industrial economy.

(d) Liberalisation: Industrial Policy Statement 1991

Finally in 1991 the Indian government announced a shift in its industrial policy to remove controls and licences, moving to a liberalised economy permitting a much larger role to the private sector. The share of the public sector was to be reduced through a policy of disinvestment and closure of sick units. This created a sea change in the economic outlook of the country, particularly from the point of view of the consumers. It is not merely that the aspirations of the growing middle class for a better standard of living in terms of availability of goods and services have been met. Even the lower income families could now buy such goods.

On the positive side, liberalisation has certainly made India a more attractive destination for foreign investment. State governments are keen to advertise that they are relaxing restrictions to improve the ease of doing business in their state. All this has created a general air of prosperity which is reflected in the growth statistics of the economy as a whole.

On the negative side, liberalisation and globalisation have resulted in a significant increase in income disparities between the top income groups and the lower income groups. The removal of ceilings on corporate salaries has widened the disparities between the salaried class of corporate executives and wage earners. The formal sector has very limited potential for additional employment and most of the new employment is generated in the informal sector, and disparities have also increased across these two sectors.

However, neither the advocates of a free economy nor leftist economists are happy with the level of liberalisation. The former want more free play of market forces to eradicate imbalances and checks to progress which are still in place. The leftists are unhappy that the state has abdicated its responsibility of ensuring and promoting social justice and welfare by allowing free play to private capitalists to exploit the economy.

Five Year Plans

India followed the example of the USSR in planning for development through five year plans. The Planning Commission was set up in 1950 to formulate plans for developing the economy. Each Plan assessed the performance of the economy and the resources available for future development. Targets were set in accordance with the priorities of the government. Resources were allocated to various sectors, like agriculture, industry, power, social sectors and technology, and a growth target was also set for the economy as a whole. One of the primary objectives of planning was to build a self-sufficient economy.

The First Five Year Plan covered the period 1951–56. Till now there have been twelve Five Year Plans in addition to three one year plans between 1966 and 1969.

The proposed outlays for a Plan take both private and public sector outlays into account. The total outlay proposed for the First Plan was ₹ 3870 crores. By the Eleventh Plan, it had crossed ₹ 36.44 lakh crores, which is an indication of the extent to which the Indian economy had grown in less than sixty years. Between the Second and Sixth Plans, public sector accounted for 60 to 70% of the total plan outlay. But since then, the share of the public sector gradually came down, and private sector began to dominate in total plan outlay.

The First Plan (1951–56) focused on developing agriculture, especially increasing agricultural production. The allocation for Agriculture and Irrigation accounted for 31% of the total outlay. After this, the emphasis shifted to industry, and the share of agriculture in total outlay hovered between 20 and 24%. By the Eleventh Plan it had come down to less than 20%. The Second Plan (1956–61), commonly referred to as the Mahalanobis Plan, stressed the development of heavy industry for achieving economic growth. The share of industry in Plan outlay was only 6% in the First Plan, and increased to about 24% after the Second Plan. But the share has been declining since the Sixth Plan, perhaps because the major investments in the public sector had been completed. The allocation for power development was very low in the first four plans and this created a huge shortage of power in the country.

The first two Plans had set fairly modest targets of growth at about 4%, which economists described as the “Hindu rate of growth”. These growth rates were achieved so that the first two Plans were considered to have been successful. The targets in subsequent plans were not achieved due to a variety of factors. From the Fourth Plan (1969–74) the emphasis was on poverty alleviation, so that social objectives were introduced into the planning exercise. The targeted growth rates were reached from the Sixth Plan onwards.

The economy was liberalised during the Eighth Five Year Plan (1992–97) . Since then, the growth rates have been in excess of 7% (except for a slowdown in the Ninth Plan).There has been considerable emphasis on growth with justice, and inclusive and sustainable growth.

There are positive and negative assessments of the performance of planning in India.

Achievements

1. The expansion of the economy

2. The significant growth in national and per capita income

3. Increase in industrial production

4. Increased use of modern inputs in agriculture and increase in agricultural production

5. A more diversified economy.

Education, Science and Technology

(a) Education

Education and health constitute the social sectors, and the status of education and health indicators are yardsticks for assessing the level of social development in a country. Literacy levels have increased in India from 18.3% in 1951 to 74% in 2011. Female literacy still lags behind the male literacy rate at 65% as compared to 82% among men. There has been a great increase in the number of schools from the primary to senior high school level and in the growth of institutions of higher learning. In 2014 – 15 there were 12.72 lakh primary and upper primary schools, 2.45 lakh secondary and higher secondary schools, 38,498 colleges and 43 Central Universities, 316 State Universities, 122 Deemed Universities and 181 State Private Universities in the country.

Children dropping out of school mostly belonged to the poorer families in rural and urban areas. The drop-out rate is particularly high among girl children. There are great inter-regional variations in the drop-out and enrolment rates, so that backward states and regions have the poorest record on school education. Various initiatives are being taken by the government to such as Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) and the recently integrated scheme of Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan to redress the issue of dropouts.

(b) Science and Technology

India has made great strides in developing institutions of scientific research and technology. The only science research institute in India before Independence was the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) established in 1909 in Bangalore with funding from J.R.D. Tata and the Maharaja of Mysore.

The Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) was set up in 1945 on the initiative of Homi J. Bhabha, with some funding from the Tatas. It was intended to promote research in mathematics and pure sciences. The National Chemical Laboratory, Pune and the National Physics Laboratory, New Delhi were the first institutes set up in India around the time of Independence. Since then there has been a steady increase in the number of institutes doing research in pure sciences, ranging from astrophysics, geology/ geo-physics, cellular and molecular biology, mathematical sciences and so on.

The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) is the umbrella organisation under which most of the scientific research institutions function. The CSIR also advances research in applied fields like machinery, drugs, planes etc.

The Atomic Energy Commission is the nodal agency for the development of nuclear science which is strategically important, focusing both on nuclear power generation and nuclear weapons. The Atomic Energy Commission also funds several institutes of pure science research.

Agriculture is another area where there has been a significant expansion of research and development. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) is the coordinating agency for the research done not only in basic agriculture, but also associated activities like fishery, forests, dairy, plant genetics, bio-technology, varieties of crops like rice, potato, tubers, fruits and pest control. Agricultural universities are also actively engaged in teaching and research on agricultural practices. There are 67 agricultural universities in India, and 3 in Tamil Nadu.

Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) were set up as centres of excellence in different fields of engineering. The first IIT was located in Kharagpur, followed by Delhi, Bombay, Kanpur and Madras (Chennai). There are now 23 IITs in the country, in addition to 31 NITs (National Institutes of Technology) and about 23 IIITs (Indian Institutes of Information Technology).

In spite of advances, the general perception is that science research in India still has a long way to go to catch up with the more developed countries and China. The research output in theoretical fields is rather disappointing and scanty in spite of the number of research institutions in the country.