Introduction

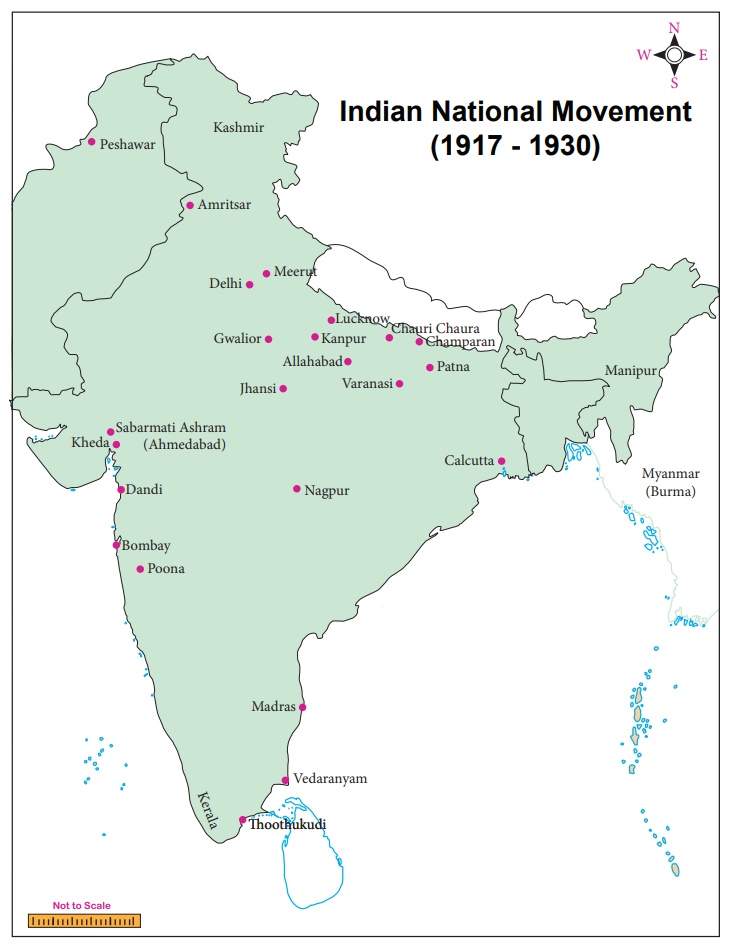

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born in the coastal town of Porbandar in 1869. When he returned to India in 1915 he had a record of fighting against inequalities imposed by the racist government of South Africa. Gandhi certainly wanted to be of help to forces of nationalism in India. He was in touch with leaders India as he had come into contact with Congress leaders while mobilizing support for the South African Indian cause earlier. Impressed by activities and ideas of Gopala Krishna Gokhale, he acknowledged him as his political Guru. On his return to India, following Gokhale’s advice, Gandhi, who was away from India for over two decades, spent a year travelling all over the country acquainting himself with the situation. He established his Sabarmati Ashram at Ahmedabad but did not take active part in political movements including the Home Rule movement.

While in South Africa, Gandhi, gradually evolved the technique of ‘Satyagraha,’ based on Satya’ and ‘Ahimsa’ i.e, truth and non-violence, to fight the racist South African regime. Even while resisting evil and wrong a Satyagrahi had to be at peace with himself and not hate the wrongdoer. A Satyagrahi would willingly accept suffering in the course of resistance, and hatred had no place in the exercise. Truth and nonviolence would be weapons of the brave and fearless and not cowards. For Gandhi there was no difference between precept and practice, faith and action.

Gandhi’s Experiments of Satyagraha

a) Champaran Movement (1917)

The first attempt at mobilizing the Indian masses was made by Gandhi on an invitation by peasants of Champaran. Before launching the struggle he made a detailed study of the situation. Indigo cultivators of the district Champaran in Bihar were severely exploited by the European planters who had bound the peasants to compulsorily grow indigo on lease on 3/20th of their fields and sell it at the rates fixed by the planters. This system squeezed the peasants and eventually reduced them to penury. Accompanied by local leaders such as Rajendra Prasad, Mazharul Huq, Acharya Kripalani and Mahadeva Desai, Gandhi conducted a detailed enquiry. The British officials ordered Gandhi to leave the district. But he refused and told the administration that he would defy the order because it was unjust and face the consequences.

Subsequently an enquiry committee with Gandhi also as a member was formed. It was not difficult for Gandhi to convince the committee of the difficulties of the poor peasants. The report was accepted and implemented resulting in the release of the indigo cultivators of the bondage of European planters who gradually had to withdraw from Champaran itself.

b) Mill Workers’ Strike and Gandhi’s Fast at Ahmedabad (1918)

Thus Gandhi met with his first success in his homeland. The struggle also enabled him to closely understand the condition of peasantry. The next step at mobilizing the masses was the workers of the urban centre, Ahmedabad. There was a dispute between the textile workers and the mill owners. He met both the parties and when the owners refused to accept the demands of the low paid workers, Gandhi advised them to go on strike demanding a 35 percent increase in their wages. To bolster the morale of the workers he went on fast. The worker’s strike and Gandhi’s fast ultimately forced the mill owners’ to concede the demand.

(c) The Kheda Struggle (1918)

The peasants of Kheda district, due to the failure of monsoon, were in distress. They had appealed to the colonial authorities for remission of land revenue during 1918. As per government’s famine code, in the event of crop yield being under 25 percent of the average the cultivators were entitled for total remission. But the authorities refused and harassed them demanding full payment. The Kheda peasants who were also battling the plague epidemic, high prices and famine approached the Servants of India Society, of which Gandhi was a member, for help. Gandhi, along with Vithalbhai Patel, intervened on behalf of the poor peasants and advised them to withhold payment and ‘fight unto death against such a spirit of vindictiveness and tyranny.’ Vallabhbhai Patel, a young lawyer and Indulal Yagnik joined Gandhi in the movement and urged the ryots to be firm. The government repression included attachment of crops, taking possession of the belongings of the ryots and their cattle and in some cases auctioning them.

The government authorities issued instructions that revenues shall be collected only from those ryots who could afford to pay. On learning about the same, Gandhi decided to withdraw the struggle.

The three struggles led by Gandhi, demonstrated that he had understood where the Indian nation lay. It was the poor peasants and workers of all classes and castes, who constituted the pith and marrow of India, whose interests Gandhi espoused in these struggles. He had confronted both the colonialist and Indian exploiters and by entering into dialogue with them, he had demonstrated that he was a leader who could mobilize the oppressed and at the same time negotiate with the oppressors. These virtues made him the man of the masses and soon he was hailed as the Mahatma.

Servants of India Society was founded by Gopal Krishna Gokhale in 1905 to unite and train Indians of different castes, regions and religions in welfare work. It was the first secular organization in the country to devote itself to the betterment of underprivileged, rural and tribal people. The members involved themselves in relief work, the promotion of literacy, and other social causes. Members would have to go through a five-year training period and agree to serve on modest salaries. The organization has its headquarters in Pune (Maharashtra) and notable branches in Chennai (Madras), Mumbai (Bombay), Allahabad and Nagpur.

Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms

Edwin Montagu and Chelmsford, the Secretary of State for India and Viceroy respectively, announced their scheme of constitutional changes for India which came to be known as the Indian Councils Act of 1919. The Act enlarged the provincial legislative councils with elected majorities. The governments in the provinces were given more share in the administration under ‘Dyarchy.’ Under this arrangement all important subjects like law and order and finance ‘reserved’ for the whitemen and were directly under the control of the Governors. Other subjects such as health, educations and local self-government were ‘transferred’ to elected Indian representatives. Ministers holding ‘transferred subjects’ were responsible to the legislatures; but those in-charge of ‘reserved’ subjects were not further the Governor of the province could overrule the ministers under ‘special (veto) powers,’ thus making a mockery of the entire scheme. The part dealing with central legislature in the act created two houses of legislature (bicameral).

The Central Legislative Assembly was to have 41 nominated members, out of a total of 144. The Upper House known as the Council of States was to have 60 members, of whom 26 were to be nominated. Both the houses had no control over the Governor General and his Executive Council. But the Central Government had full control over the provincial governments. As a result, power was concentrated in the hands of the European / English authorities. Right to vote also continued to be restricted.

The public spirited men of India, who had extended unconditional support to the war efforts of Britain had expected more. The scheme, when announced in 1918, came to be criticized throughout India. The Indian National Congress met in a special session at Bombay in August 1918 to discuss the scheme. The congress termed the scheme ‘disappointing and unsatisfactory.’

The colonial government followed a ‘carrot and stick policy.’ There was a group of moderate / liberal political leaders who wanted to try and work the reforms. Led by Surendranath Banerjee, they opposed the majority opinion and left the Congress to form their own party which came to be called Indian Liberal Federation.

The Non-Brahmin Movement

The hierarchical Indian society and the contradictions within, found expression in the formation of caste associations and movements to question the dominance of higher castes. The higher castes also were controlling the factors of production and thus the middle and lower castes were dependent on them for livelihood. Liberalism and humanism which influenced and accompanied the socio-religious reform movements of the nineteenth century had affected the society and stirred it. The symptoms of their awakening were already visible in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The Namasudra movement in the Bengal and eastern India, the Adidharma movement in North Western India, the Satyashodhak movement in Western India and the Dravidian movements in South India had emerged and raised their voice by the turn of the century. They were all led by non Brahmin leaders who questioned the supremacy of the Brahmins and other ‘superior’ castes.

It first manifested itself, through Jyoti Rao Phule’s book of 1872 titled Gulamgiri. His organization, Satyashodak Samaj, underscored the necessity to relieve the lower castes from the tyranny of Brahminism and the exploitative scriptures. The colonial administrators and the educational institutions that were established indirectly facilitated their origin. Added to the growing influence of Brahmin – upper caste men in the colonial times in whatever opportunity was open to natives, the colonial government published census reports once a decade. These reports classified castes on the basis of ‘social precedence as recognized by native public opinion’. The censuses were a source of conflict between castes. There were claims and counterclaims as the leaders of caste organizations fought for pre-eminence and many started new caste associations. These attempts were further helped by the emerging political scenario.

Leading members of castes realized that it was important to mobilise their castes in struggles for social recognition. More than the recognition, many of them their caste brethren and helped their educated youth in getting jobs. In the meantime, introduction of electoral politics from the 1880s gave a fillip to such organisations. The outcome of all this was the expression of socio-economic tensions through caste consciousness and caste solidarity.

Two trends emerged out of the non-Brahmin movements. One was what is called the process of ‘Sanskritisatian’ of the ‘lower’ castes and the second was a radical pro-poor and progressive peasant–labour movements. While the northern and eastern caste movements by and large were Sanskritic, the western and southern movements split and absorbed by the rising nationalist and Dravidian–Left movements. However all these movements were critical of what they called as ‘Brahmin domination’ and attacked their ‘monopoly’, and pleaded with the government through their associations for justice. In Bombay and Madras presidencies clear-cut Brahmin monopoly in the government services and general cultural arena led to non-Brahmin politics.

The pattern of the movement in south was a little different. The Brahmin monopoly was quite formidable as with only 3.2% of the population they had 72% of all graduates. They came to be challenged by educated and trading community members of the non-Brahmin castes. They were elitist in the beginning and their challenge was articulated by the Non-Brahmin Manifesto issued at the end of 1916. They asserted that they formed the ‘bulk of the tax payers, including a large majority of the zamindars, landlords and agriculturists’, yet they received no benefits from the state.

The colonial government made use of the genuine grievances of the non-Brahmins to divide and rule India. This was true with the Brahmanetara Parishat, and Justice Party

Of Bombay and Madras presidencies respectively at least till 1930. Both the regions had some socially radical possibilities as could be seen in the emergence of a radical Dalit-Bahujan movement under the leadership of Dr Ambedkar and the Self-Respect Movement under the leadership of Periyar Ramaswamy.

The nationalists were unable to understand the liberal democratic content in the awakening among the lower strata of Indian society. While a section of the nationalists simply ignored the stirrings, a majority of them and particularly the so-called extremists–radicals were opposed to the movements. A few of them were even hostile and labelled them as stooges of British, anti-national etc. The early leaders of the non-Brahmin movement were in fact using the same tactics as the early nationalist leaders in dealing with the colonial government.

Non-cooperation Movement

(a) Rowlatt Act

It was as part of the British policy of ‘rally the moderates and isolate the extremists’ that the Indian Councils Act 1919 and the Rowlatt Act of the same year were promulgated. Throughout the World War, the repressive measures against the terrorists and revolutionaries had continued. Many of them were hanged or imprisoned for long terms. As the general mood was restive, the government decided to arm itself with more repressive powers. Despite every elected member of the central legislature opposing the bill, the government passed the Rowlatt Act in March 1919. This Act empowered the government to imprison any person without trial.

Gandhi and his associates were shocked. It was the ‘Satyagraha Sabha’ founded by Gandhi, which pledged to disobey the Act first. In the place of the old agitational methods such as meetings, boycott of foreign cloth and schools, picketing of toddy shops, petitions and demonstrations, a novel method was adopted. Now ‘Satyagraha’ was the weapon to be used with the wider participation of labour, artisan and peasant masses. The symbol of this change was to be khadi, which soon became the uniform of nationalists. India’s Swaraj would be a reality only when the masses awakened and became active in political work. Almost the entire country was electrified when Gandhi called upon the people to observe ‘hartal’ in March–April 1919 against the Rowlatt Act. He combined it with the Khilafat issue which brought together Hindus and Muslims.

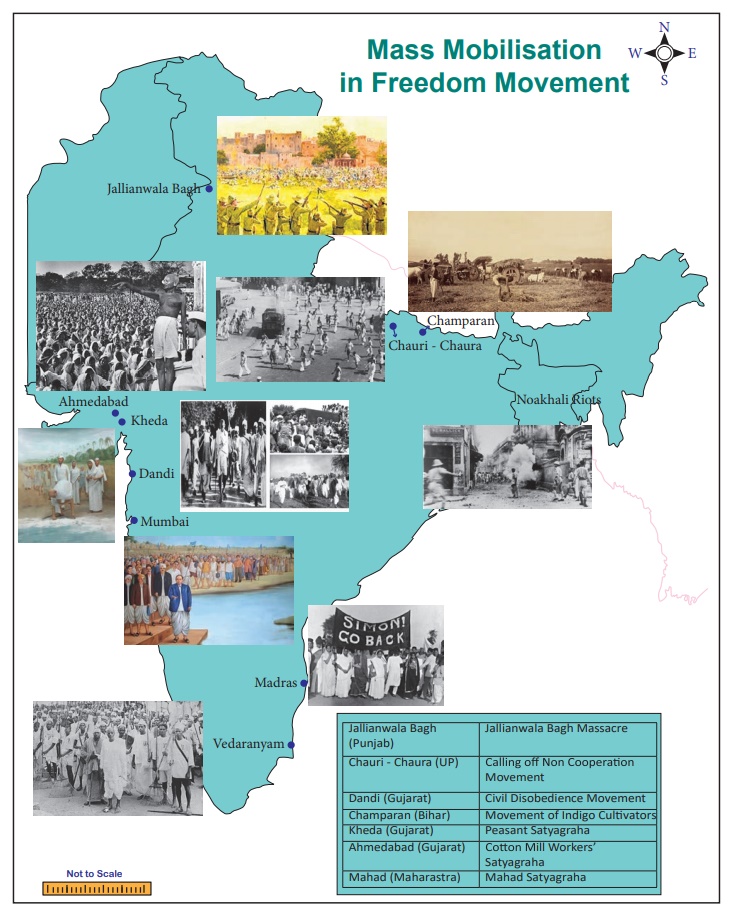

(b) Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre

The colonial government was enraged at the mass struggles and the enthusiasm of the masses as evidenced in the upsurge all over the country. On 13th April 1919, in Amritsar town, in the Jallianwala enclave that the most heinous of political crimes was perpetrated on an unarmed mass of people by the British regime. More than two thousand people had assembled at the venue to peacefully protest against the arrest of their leaders Satyapal and Saifudding Kitchlew. Michael O’Dwyer was the Lt. Governor of Punjab and the military commander was General Reginald Dyer. They decided to demonstrate their power and teach a lesson to the dissenters. The part where the gathering was held had only one narrow entrance. Dyer ordered firing on the trapped crowd with machine guns and rifles till the ammunition was exhausted. While the official figures of the dead was only about 379 the real number was over a thousand. Martial law was imposed all over Punjab and people were subject to untold indignities.

The entire country was horrified at the brutalities. In Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi, Lahore there were widespread protests against the Rowlatt Act where the protesters were fired upon. There was violence in many towns and cities. Protesting against the brutalities many celebrities renounced their titles, of whom Ravindranath Tagore was one.

Rabindranath Tagore renounced his knighthood immediately after the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre. In his protest letter to the viceroy on May 31, 1919, Tagore wrote “The time has come when the badge of honour makes our shame glaring in their incongruous context of humiliation, and, I for my part, wish to stand shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who for their so-called insignificance are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.”

The two immediate causes responsible for launching the non-cooperation movement were the Khilafat and the Punjab wrongs. While the khilafat issue related to the position of the Turkish Sultan vis-a- vis the holy places of Islam, the Punjab issue related to the exoneration of the perpetrators of the Jallianwala massacre. While the control over holy places of Islam was taken over by non-Islamic powers against the assurances of the British rulers, the British courts of enquiry totally exonerated Reginald Dyer and Michael O’Dwyer of the crime perpetrated at Jallianwala. Gandhi and the Congress, who were bent upon Hindu-Muslim unity, now stood by their Muslim compatriots who felt betrayed by the British regime. The Ali brothers – Shukha and Muhammed – and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad were the prime movers in the Khilafat movement.

A Sikh teenager who was raised at Khalsa Orphanage named Udham Singh saw the happening in his own eyes. To avenge the killings of Jallianwalla Bagh, on 30 March 1940, he assassinated Michael O’Dwyer in Caxton Hall of London. Udham Singh was hanged at Pentonville jail, London

Gandhi and the Congress, who were bent upon Hindu-Muslim unity, now stood by their Muslim compatriots who felt betrayed by the British regime. The Ali brothers – Shukha and Muhammed – and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad were the prime movers in the Khilafat movement.

(c) Launch of Non-Cooperation Movement

The Khilafat Conference, at the instance of Gandhi, decided to launch the non-cooperation movement from 31 August 1920. Earlier an all party meet at Allahabad had decided on a programme of boycott of government educational institutions and their law courts. The Congress met in a special session at Calcutta in September 1920 and resolved to accept Gandhi’s proposal on non-cooperation with the colonial state till such time as Khilafat and Punjab grievances were redressed and self-government established.

Non-cooperation movement included boycott of schools, colleges, courts, government offices, legislatures, foreign goods, return of government conferred titles and awards. Alternatively, national schools, panchayats were to be set up and swadeshi goods manufactured and used. The struggle at a later stage was to include no tax campaign and mass civil disobedience, etc. A regular Congress session held at Nagpur in 1920 endorsed the earlier resolutions. Another important resolution at Nagpur was to recognize and set up linguistic Provincial Congress Committees which drew a large number of workers into the movement. In order to broad base the Congress, the workers were to reach out to the villages and enroll the villagers in the Congress on a nominal fee of four annas (25 paise). The overall character of the Congress underwent change and an atmosphere where a large majority of the masses could develop a sense of belonging to the nation and the national struggle developed. But it also led to some conservatives who were opposed to mass participation in the struggle to leave the Congress. Thus the Congress under Gandhi was shedding its elitist character, becoming a mass organization and in a real sense ‘National’.

(d) Impact of Gandhi’s Leadership

Thousands of schools and hundreds of colleges and vidyapeethas were established by the natives as alternatives to the government institutions. Several leading lawyers gave up their practice. Thousands of school and college students left the government institutions. The Ali brothers were arrested and jailed on sedition charges. The Congress committees called upon people to launch civil disobedience movement, including no tax movements if the Congress committees of their region were ready. The government as usual resorted to repression. Workers were arrested indiscriminately and put behind bars. The visit of Prince of Wales in 1921 to several cities in India was also boycotted. The calculation of the colonial government that the visit of the Prince would evoke loyal sentiments of the Indian people was proved wrong.

Workers and peasants had gone on strike across the country. Gandhi promised Swaraj, if Indians participated in the non-cooperation movement on non-violent mode within a year.

South India surged forward during this phase of the struggle. The peasants of Andhra, withheld payment of taxes to the zamindars and the whole population of Chirala-Perala refused to pay taxes and vacated the town en-mass. Hundreds of village Patels and Shanbogues resigned their jobs. Non-Cooperation movement in Tamil Nadu was organised and led by stalwarts like C. Rajagopalachari, S. Satyamurthi and Periyar E.V.R. In Kerala, peasants organized anti-jenmi struggles.

The Viceroy admitted in a letter to the Secretary of State that the movement had seriously affected lower classes in certain areas of UP, Bengal, Assam, Bihar and Orissa the peasants have been affected. Impressed by the intensity of the movement, in a special session the Congress reiterated the intensification of the movement.In February 1922 Gandhi announced that he would lead a mass civil disobedience, including no tax campaigns, at Bardoli, if the government did not ensure press freedom and release the prisoners within seven days.

(e) Chauri Chaura Incident and Withdrawal of the Movement

The common people and the nationalist workers were exuberant that Swaraj would dawn soon and participated actively in the struggle. It had attracted all classes of people including the tribals living in the jungles. But at the same time sporadic violence was also witnessed along with arson. In Malabar and Andhra two very violent revolts also took place. In the Rampa region of coastal Andhra the tribals revolted under the leadership of Alluri Sitarama Raju. In Malabar, Muslim (Mapilla) peasants rose up in armed rebellion against upper caste landholders and the British government.

Chauri-Chaura, a village in Gorakhpur district of UP had an organized volunteer group which was participating and leading the picketing of liquor shops and local bazaar against high prices. On 5 February 1922, a Congress procession, 3000 strong, was fired upon by police Enraged by the firing, the mob attacked and burnt down the police station. 22 policemen lost their lives. It was this incident which made Gandhi announce the suspension of the non-cooperation movement.

The Congress Working Committee ratified the decision at Bardoli, to the disappointment of the nationalist workers. While the younger workers resented the decision, the others who had faith in Gandhi considered it a tactical retreat. Both Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose were critical of Gandhi, who was arrested and sentenced to 6 years in prison. Thus ended the non-cooperation movement.

The Khilafat issue was made redundant when the people of Turkey under the leadership of Mustafa Kamal Pasha rose in revolt and stripped the Sultan of his political power and abolished the Caliphate and declared that religion and politics could not go together.

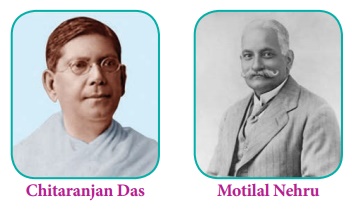

Swarajist Party and its Activities

Following the suspension of Non-cooperation the question was what next? Chittaranjan Das and Motilal Nehru proposed a new line of activity. They wanted to return to active politics which included entry into electoral politics and demonstrate that the nationalists were capable of obstructing the working of the reformed legislature by capturing them and arousing nationalist spirit. This group came to be called the ‘Swarajists and pro-changers’. In Tamil Nadu, Satyamurti joined this group.

There was another group which opposed council entry and wanted to continue the Gandhian line by mobilizing the masses. This team led by Rajagopalachari,Vallabhai Patel and Rajendra Prasad was called ‘No changers.’ They argued that electoral politics would divert the attention of nationalists and pull them away from the work of mass mobilization and their issues. They favoured the continuation of the Gandhian constructive programme of spinning, temperance, Hindu-Muslim unity, removal of untouchability and mobilise rural masses and prepare them for new mass movements. The pro -changers launched the Swarajya party as a part of the Congress. A truce was soon worked out and both the groups would engage themselves in the Congress programmes and their work should complement each other’s activities under the leadership of Gandhi, though Gandhi personally favoured constructive work.

The Swarajya party did reasonably well in the elections to Central Assembly by winning 42 of the 101 seats open for election. With the cooperation of other members they were able to stall many anti-people legislations of the colonial regime, and were successful in exposing the inadequacy of the Act of 1919. But their efforts and enthusiasm petered out as time passed by and consciously or unconsciously they came to be co-opted by the Government as members of several committees constituted by it.

In the absence of nationalist mass struggle, fissiparous tendencies started rising their head. There were a series of communal riots with fundamentalist elements occupying the space. Even the Swaraj party was affected by the sectarianism as one group in the name of ‘responsivists’ started cooperating with the government, claiming to safeguard “Hindu interests”. The Muslim fundamentalists similarly seized the space created by the lull in national struggle and started fanning communal feeling. Rise of Left Radicalism Gandhi was pained at the developments. To contain the communal frenzy he went on a 21 day fast.

Left Movement

Meanwhile socialist ideas and its activists also had filled some space through their work among peasants and workers. The labour and peasant movements were organized by the ‘leftists’. Marxism as an ideology to criticise colonialism and capitalism had gained ground. It manifested itself in the organization of students and youth apart from trade unions. Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose contributed to the spread of leftist ideology. They argued that both colonial exploitation and the internal exploitation by the emerging capitalists should be fought. A group of youngsters with S A. Dange, M.N Roy, Muzaffar Ahmed along with elderly persons such as Singaravelu form Tamilnadu founded the peasants and worker’s parties. The government came down heavily on the communist-socialists and the revolutionaries a series of ‘conspiracy cases’ such as Kanpur, Meerut, Kakori were booked.

It was at this juncture Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekar Azad, Rajguru and Sukhdev emerged on the scene. The Naujawan Bharat Sabha, Hindustan Republican Association were started and thousands of youngmen and women became active anti-colonialists and revolutionaries. Youth and student conferences were organized all over the country. Meanwhile Ramprasad Bismil and Ashfaq-ullah were convicted to death and 17 others were sentenced to long term imprisonment in the Kakori conspiracy case. Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekar Azad and Rajguru, enraged at the police brutality and death of Lajpat Rai, killed Saunders, the British police officer who led the lathi charge at Lahore. Bhagat Singh and Batukeswar Dutt threw a bomb into the central Assembly hall on 8 April 1929. In 1929 the Meerut conspiracy case was filed and three dozen communist leaders were sentenced to long spells of jail terms. All these developments and incidents are discussed in detail in the next lesson.

Simon Commission – Nehru Report – Lahore Congress

The British were due to consider and announce another instalment of constitutional reforms some time in 1929–30. In preparation, it announced the setting up of Indian Statutory commission (known as ‘Simon Commission’ after its chairman). The commission had only whitemen as members and it was an insult to Indians. The Congress at it annual session in Madras in 1927 resolved to boycott the commission. The Muslim league and the Hindu Mahasabha also supported the decision. A series of conferences were held and the consensus was to work for an alternative proposal. Most of the parties agreed to challenge the colonial attitude towards India and the result was the Motilal Nehru Report. However the All-Parties meet held in 1928 December at Calcutta failed to accept it on the issue of communal representation.

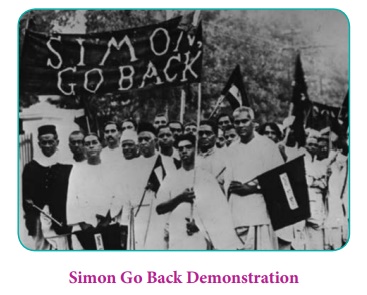

Simon Go Back

But the most important development was the popular protest against the Simon Commission. Whenever the commission went protests were held and the slogan ‘Simon Go Back’ rent the air. The movement demonstrated that the masses were gearing up for the next stage of the struggle. It was at Calcutta that the Congress met in December 1928. To conciliate the left wing it was announced that Jawaharlal would be the President of the next session in 1929. Thus Jawaharlal Nehru, son of Motilal Nehru, who presided over Congress in 1928, succeeded his father.

Lahore Congress Session – Poorna Swaraj

Lahore session of the Congress has a special significance in the history of the freedom movement. It was at the Lahore session that the Congress declared that the objective of the Congress was the attainment of complete independence. On 31 December 1929 the tricolour flag of freedom was hoisted at Lahore. It was also decided that 26 January would be celebrated as the Independence day every year. It was also announced that civil disobedience would be started under the leadership of Gandhi.

Dandi March

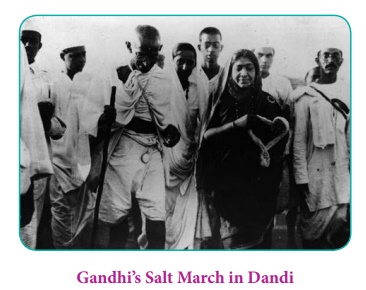

As a part of the movement Gandhi announced the ‘Dandi March’. It was a protest against the unjust tax on salt, which is used by all. But the colonial government was taxing it and had a near monopoly over it. The Dandi March was to cover 375 kms from Gandhi’s Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi on the Gujarat coast. Joined by a chosen band of 78 followers from all regions and social groups, after informing the colonial government in advance, Gandhi set out on the march and reached Dandi on the 25th day i.e. 6 April 1930. Throughout the period of the march the press covered the event in such a way that it had caught the attention of the entire world. He broke the salt law by picking up a fist full of salt. It was symbolic of the refusal of Indians to be under the repressive colonial government and its unjust laws.

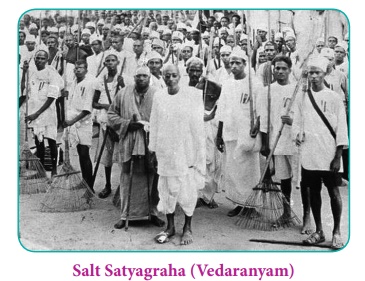

Vedaranyam Salt Satyagraha

In Tamilnadu, a salt march was led by Rajaji to Vedaranyam. Vedaranyam, situated 150 miles from Tiruchirapalli from where march started was an obscure coastal village in Thanjavur district. Rajaji had just been elected president of the Tamilnadu Congress. The march started on 13th April and reached Vedaranyam on 28th April 1930.

The Thajavur collector J.A Thorne had warned the public of severe action if the marchers were harboured. But the Satyagrahis were warmly welcomed and provided with food and shelter. Those who dared to offer food and shelter were severely dealt with. The Satyagrahis marched via Kumbakonam, Semmangudi, Thiruthuraipoondi where they were given good reception.

The Vedaranyam movement stirred the masses in south India and awakened them to the colonial oppression and the need to join the struggle.

The Round Table Conferences

The Simon Commission had submitted the report to the government. The Congress, Muslim league and Hindu Mahasabha had boycotted it. The British regime went ahead with the consideration of the report. But in the absence of consultations with Indian leaders it would have been useless. In order to secure some legitimacy and credibility to the report, the government announced that it would convene a Round Table Conference (RTC) in London with leaders of different shades of Indian opinion. But the Congress decided to boycott it, on the issue of granting independence. Everyone knew, more so the government, that it would be an exercise in futility if the Congress did not participate.

Thus negotiations with Congress were started and the Gandhi-Irwin pact was signed on March 5, 1931. It marked the end of civil disobedience in India. The movement had generated worldwide publicity, and Viceroy Irwin was looking for a way to end it. Gandhi was released from custody in January 1931, and the two men began negotiating the terms of the pact. In the end, Gandhi pledged to give up the satyagraha campaign, and Irwin agreed to release tens of thousands of Indians who had been jailed during the movement.

That year Gandhi attended the Second Round Table Conference in London as the sole representative of the Congress. The government agreed to allow people to make salt for their consumption, release political prisoners who had not indulged in violence, and permitted the picketing of liquor and foreign cloth shops. The Karachi Congress ratified the Gandhi–Irwin pact. However the Viceroy refused to commute the death sentence of Bhagat Singh and his comrades.

Gandhi attended the Second RTC but the government was adamant and declined to concede his demands. He returned empty handed and the Congress resolved on renewing the civil disobedience movement. The economic depression had worsened the condition of the people in general and of the peasants in particular. There were peasant protests all over the country. The leftists were in the forefront of the struggles of the workers and peasants. The government was determined to crush the movement. All key leaders including Nehru, Khan Abdul Gafar Khan and finally Gandhi were all arrested. The Congress was banned. Special laws were enacted to crush the agitations. Over a lakh of protesters were arrested and literature relating to nationalism was also declared illegal and confiscated. It was a reign of terror that was unleashed on the unarmed masses participating in the movement.

The movement started waning and it was officially suspended in May 1933 and withdrawn in May 1934.

Emergence of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and the Separate Electorates

Dr. Ambedkar came to the centre stage of the struggles of the oppressed world in the 1920’s. Born in the then so-called “untouchable” caste called Mahar in Central India as the son of an army man, he was a brilliant student and was the first to matriculate from his community.

Ambedkar’s Academic Accomplishments

Ambedkar joined the Elphinston College, with the help of a scholarship and graduated in 1912. With the help of a scholarship from the Maharaja of Barona he went to United States and secured a post-graduate degree, and doctorate, from the Columbia University. Then he went to London to study law and economics.

Ambedkar’s brilliance caught the attention of many. Already in 1916, he had participated in an international conference of Anthropology and presented a research paper on ‘Castes in India’, which was published later in the Indian Antiquary. The British government which wassearching for talents among the downtrodden of India invited him to interact with the Southborough or the Franchise Committee which was collecting evidence on the quantum and qualifications to be fixed for the Indian voters.

It was in these interactions that Ambedkar first spoke about separate electorates. He argued the untouchables be given separate electorates and reserved seats. Under this scheme only untouchables could vote in the constituencies reserved for them. Ambedkar felt that if any untouchable candidate contesting elections were to depend on non-untouchable voters he or she would be more obliged to the latter and would not therefore be in a position to worker at freely for the good of the untouchables. If only untouchable voters were to vote and elect in the reserved seats, those elected would be their real representatives.

Ambedkar’s Activism

Ambedkar launched news journals and organizations. Mook Nayak (leader of the dumb) was the journal to articulate his views and the Bahishkrit Hitakarini Sabha (Association for thewelfare of excluded) spearheaded his activities. As a member of the Bombay legislative council he worked tirelessly to secure removal of disabilities imposed on untouchables. He launched the ‘Mahad Satyagraha’ to establish the civic right of the untouchables to public tanks and wells. Ambedkar’s intellectual and public activities drew the attention of all concerned. His intellectual attacks were directed against leaders of the Indian National Congress and the colonial bureaucracy. In the meanwhile the struggle for freedom under Congress and Gandhi’s leadership had reached a decisive phase with their declaration that their objective was to fight for complete independence or ‘Purna Swaraj’.

Ambedkar on Separate Electorate for “Untouchables”

Ambedkar was concerned about the future of “untouchables” and the oppressed in an independent India which was certain to be under the control of Congress under the hegemony of the caste Hindus. He renewed his demand for separate electorates, be it before the All-Parties conference or the Simon commission or at the Round Table Conference. The Congress and Gandhi were worried that separate electorates for untouchables would further weaken the national movement, as separate electorates to Muslims, Anglo Indians and other special interests had helped the British to successfully pursue its divide and rule policy. Gandhi feared that the separation of untouchables from other Hindus politically would also have its social impact.

Communal Award

A meeting between Gandhi and Ambedkar on this issue of separate electorates before they went to London to attend the Second Round Table Conference ended in failure. There was an encounter between the two again in the RTC about the same issue. It ended in a deadlock and finally the issue was left to be arbitrated by the British Prime Minister Ramsay McDonald. The British government announced in August 1932 what came to be known as the Communal Award. Ambedkar’s demands for separate electorates with reserved seats were conceded.

Poona Pact

Gandhi was deeply upset. He declared that he would resist separate electorates to untouchables ‘with his life’. He went on a fast unto death in the Yervada jail where he was imprisoned. There was enormous pressure on Ambedkar to save Gandhi’s life. Consultations, confabulations, meetings, prayers were held all over and ultimately after a meeting with Gandhi in the jail, the communal award was modified. The new agreement, between Ambedkar and Gandhians, called the ‘Poona Pact’ was signed.

The Poona Pact took away separate electorates but guaranteed reserved seats for the untouchables. The provision of reserved seats was incorporated in the constitutional changes which were made. It was also built into the Constitution of independent India.

Ambedkar and Party Politics

Ambedkar launched two political parties. The first one was the Independent Labour party in 1937 and the second Scheduled Caste Federation in 1942. The colonial government recognizing his struggles and also to balance its support base used the services of Ambedkar. Thus he was made a member of the Defence Advisory Committee in 1942, and a few months later, a minister in the Viceroy’s cabinet.

The crowning recognition of his services to the nation was electing him as the chairman of the Drafting Committee of the independent India’s Constitution. After independence Ambedkar was invited to be a member of the Nehru cabinet.