Introduction

Before the establishment of British Raj, Mughals and their agents had ruled large parts of the country. Large sections of the Muslims therefore enjoyed the advantages of being the co-religionists of the ruling class many of whom were sovereigns, landlords, the generals and officials. The official and court language was Persian. When the British gradually replaced them they introduced a new system of administration. By the mid-nineteenth century English education predominated. The 1857 rebellion was the last gasp of the earlier ruling class. Following the brutal suppression of the revolt, the Muslims lost everything, their land, their job and other opportunities and were reduced to the state of penury. Unable to reconcile to the condition to which they were reduced, the Muslims retreated into a shell. And for the first few generations after 1857 they hated everything British. Besides they resented competing with the Hindus who had taken recourse to the new avenues opened by colonialism. With the emergence of Indian nationalism especially among the educated Hindu upper castes, the British saw in the Muslim middle class a force to keep the Congress in check. They cleverly exploited the situation for the promotion of their own interests. The competing three strands of nationalism namely Indian nationalism, Hindu nationalism, and Muslim nationalism are dealt with in this lesson.

Origin and Growth of Communalism in British India

(a) Hindu Revivalism

Some of the early nationalists believed that nationalism could be built only on a Hindu foundation. As pointed out by Sarvepalli Gopal, Hindu, revivalism found its voice in politics through the Arya Samaj, founded in 1875, with its assertion of superior qualities of Hinduism. Besant identified herself with Hindu nationalists and expressed her ideas as follows: ‘The Indian work is first of all the revival, strengthening and uplifting of ancient religions. This has brought with it a new self-respect, a pride in the past, a belief in the future and as an inevitable result, a great wave of patriotic life, the beginning of the rebuilding of a nation.’

(b) Rise of Muslims Consciousness

Islam on the other hand, to quote Sarvepalli Gopal again, was securing its articulation through the Aligarh movement. The British, by building the Aligarh college and backing Syed Ahmed Khan, had assisted the birth of a Muslim national party and Muslim political ideology. The Wahabis wanted to take Islam to its pristine purity and to end the superstition which according to them had sapped its vitality. From the Wahabis to the Khilafatists, grassroots activism played a significant role in the politicization of Muslims.

Muslim consciousness developed due to other reasons as well. The Bengal government’s order in the 1870s to replace Urdu by Hindi, and the Perso- Arabic script by Nagri script in the courts and offices created apprehension in the minds of the Muslim professional group.

(c) Divide and Rule Policy of British

The object of the British was to check the development of a composite Indian identity, and to forestall attempts at consolidation and unification of Indians. The British imperialism followed the policy of Divide and Rule. Bombay Governor Elphinstone wrote, ‘Divide et Impera was the old Roman motto and itshould be ours.’ The British government lent legitimacy and prestige to communal ideology and politics despite the governance challenge that communal riots posed.

(d) Moves of the Congress

Though many congress men had involvement in Hindu organisations like Arya Samaj, the Congress leadership was secular. When there was an attempt by some Congressmen to pass a resolution in the third session of the Indian National Congress, making cow killing a penal offence, the Congress leadership refused to entertain it. The Congress subsequently resolved that if any resolution affecting a particular class or community was objected to by the delegates representing that community, even though they were in minority, it would not be considered by the Congress.

(e) Role of Syed Ahmed Khan

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, the founder of Aligarh movement was initially supportive of the Congress. Soon he was converted to the thinking that in a country governed by Hindus, Muslims would be helpless, as they would be in a minority. However, there were Muslim leaders like Badruddin Tyabji, Rahmatullah Sayani in Mumbai, Nawab Syed Mohammed Bahadur in Chennai and A. Rasul in Bengal who supported the Congress. But the majority of Muslims in north India toed the line of Syed Ahmed Khan, and preferred to support the British. The introduction of representative institutions and of open competition to government posts gave rise to apprehensions amongst Muslims and prompted Syed Ahmed Khan and his followers to work for close collaboration with the Government. By collaborating with the Government he hoped to secure for his community a bigger share than otherwise would be due according to the principles of number or merit.

The foundation of the Indian National Congress in 1885 was an attempt to narrow the Hindu-Muslim divide and place the genuine grievances of all the communities in the country before the British. But Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and other Muslim leaders like Syed Ameer Ali, the first Indian to find a place in London Privy Council, projected the Congress as a representative body of only the Hindus. Of the seventy-two delegates attending the first session of the Congress only two were Muslims. Muslim leaders opposed the Congress tooth and nail on the plea that Muslims’ participation in it would create an unfavourable reaction among the rulers against their community.

(f) Communalism in Local Body Elections

Democratic politics had the unintended effect of fostering communal tendencies. Local administrative bodies in the 1880s provided the scope for pursuing communal politics. Municipal councillors acquired vast powers of patronage which were used to build-up one’s political base. Hindus wresting the control of municipal boards from the Muslims and vice-versa led to communalisation of local politics.

Lal Chand, the principal spokesperson of the Punjab Hindu Sabha and later the leader of Arya Samaj, highlighted the extent to which some Municipalities were organised on communal lines: ‘The members of the Committee arrange themselves in two rows, around the presidential chair. On the left are seated the representatives of the banner of Islam and on the right the descendants of old Rishis of Aryavarta. By this arrangement the members are constantly reminded that they are not simply Municipal Councillors, but they are as Muhammedans versus Hindus and vice-versa….’.

(g) Weak-kneed Policy of the Congress

At the dawn of twentieth century, during the Swadeshi Movement in Bengal (1905–06), Muslim supporters of the Swadeshi movement were condemned as “Congress touts.” The silence of the Congress and its refusal to deal with such elements frontally not only provided stimulus to communal politics but also demoralized and discouraged the nationalist Muslims.

The situation took a turn for the worst in the first decade of the twentieth century when political radicalism went hand in hand with religious conservatism. Tilak, Aurobindo Gosh and Lala Lajpat Rai aroused anti-colonial consciousness by using religious symbols, festivals and platforms. The most aggravating factor was Tilak’s effort to mobilise Hindus through the Ganapati festival. Lal Chand spared no efforts to condemn the Indian National Congress of pursuing a policy of appeasement towards Muslims.

Hindu and Muslim Communalism were products of middle class infighting utterly divorced from the consciousness of the Hindu and Muslim masses. —Jawaharlal Nehru

Formation of All India Muslim League

On 1 October 1906, a 35-member delegation of the Muslim nobles, aristocrats, legal professionals and other elite sections of the community mostly associated with Aligarh movement gathered at Simla under the leadership of Aga Khan to present an address to Lord Minto, the viceroy. They demanded proportionate representation of Muslims in government jobs, appointment of Muslim judges in High Courts and members in Viceroy’s council, etc. Though the Simla deputation failed to obtain any positive commitment from the Viceroy, it worked as a catalyst for the foundation of the All India Muslim League (AIML) to safeguard the interests of the Muslims in 1907. A group of big zamindars, erstwhile Nawabs and ex-bureaucrats became active members of this movement. The League supported the partition of Bengal, demanded separate electorates for Muslims, and pressed for safeguards for Muslims in Government Service.

Objectives of All India Muslim League

The All India Muslim League, the first centrally organized political party exclusively for Muslims, had the following objectives:

- To promote among the Muslims of India feelings of loyalty to the British Government, and remove any misconception that may arise as to the instruction of Government with regard to any of its measures.

- To protect and advance the political rights and interests of Muslims of India, and to respectfully represent their needs and aspirations to the Government.

- To prevent the rise among the Muslims of India of any feeling of hostility towards other communities without prejudice to the aforementioned objects of the League.

Initially, AIML was an elitist organization of urbanized Muslims. However, the support of the British Government helped the League to become the sole representative body of Indian Muslims. Within three years of its formation, the AIML successfully achieved the status of separate electorates for the Muslims. It granted separate constitutional identity to the Muslims. The Lucknow Pact (1916) put an official seal on a separate political identity to Muslims.

Separate Electorate or Communal Electorate: Under this arrangement only Muslims could vote for the Muslim candidates. Minto-Morely Reforms, 1909 provided for eight seats to Muslims in the Imperial Legislative Council, out of the 27 non-officials to be elected. In the Legislative Council of the provinces seats reserved for the Muslim candidates were: Madras 4; Bombay 4; Bengal 5.

Separate Electorates and the Spread of Communalism

The institution of separate electorate was the principle technique adopted by the Government of British India for fostering and spreading communalism.

That the British did this with ulterior motive was evident from a note sent by one of the British officers to Lady Minto: ‘I must send your Excellency a line to say that a very big thing has happened to-day. A work of statesmanship, that will affect Indian History for many a long year. It is nothing less than pulling of 62 million people from joining the ranks of seditious opposition.’

The announcement of separate electorates and the incorporation of the principle of “divide and rule” into a formal constitutional arrangement made the estrangement between Hindus and Muslims total.

Emergence of the All India Hindu Mahasabha

In the wake of the formation of the Muslim League and introduction of the Government of India Act of 1909, a move to start a Hindu organisation was in the air. In pursuance of the resolution passed at the fifth Punjab Hindu Conference at Ambala and the sixth conference at Ferozepur, the first all Indian Conference of Hindus was convened at Haridwar in 1915. The All India Hindu Mahasabha was started there with headquarters at Dehra Dun. Provincial Hindu Sabhas were started subsequently in UP, with headquarters at Allahabad and in Bombay and Bihar. While the sabhas in Bombay and Bihar were not active, there was little response in Madras and Bengal.

Predominantly urban in character, the Mahasabha was concentrated in the larger trading cities of north India, particularly in Allahabad, Kanpur, Benares, Lucknow and Lahore. In United Province, Bihar the Mahasabha, to a large extent was the creation of the educated middle class leaders who were also activists in the Congress. The Khilafat movement gave some respite to the separatist politics of the communalists. As a result, between 1920 and 1922, the Mahasabha ceased to function.

The entry of ulema into politics led Hindus to fear a revived and aggressive Islam. Even important Muslim leaders like Ali brothers had always been Khilafatists first and Congressmen second. The power of mobilisation on religious grounds demonstrated by the Muslims during the Khilafat movement motivated the Hindu communalists to imitate them in mobilising the Hindu masses. Suddhi movement was not a new phenomenon but in the post-Khilafat period it assumed new importance. In an effort to draw Hindus into the boycott of the visit of Prince of Wales in 1921, Swami Shradhananda tried to revive the Mahasabha by organizing cow-protection propaganda.

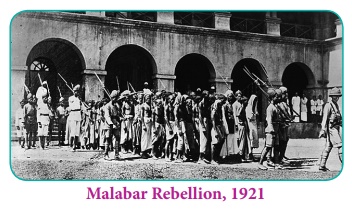

The bloody Malabar rebellion of 1921, where Muslim peasants were pitted against both the British rulers and Hindu landlords, gave another reason for the renewed campaign of the Hindu Mahasabha. Though the outbreak was basically an agrarian revolt, communal passion ran high in consequence of which Gandhi himself viewed it as a Hindu-Muslim conflict. Gandhi wanted Muslim leaders to tender a public apology for the happenings in Malabar.

Before the World War I, Britain had promised to safeguard the interests of the Caliph as well the Kaaba (the holiest seat of Islam). But after Turkey’s defeat in the War, they refused to keep their word. The stunned Muslim community showed its displeasure to the British government by starting the Khilafat movement to secure the Caliphate in Turkey.

(a) Communalism in United Provinces (UP)

The suspension of the non-cooperation movement in 1922 and the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924 left the Muslims in a state of frustration. In the aftermath of Non-Co-operation movement, the alliance between the Khilafatists and the Congress crumbled. There was a fresh spate of communal violence, as Hindus and Muslims, in the context of self-governing institutions created under the Act of 1919, began to stake their political claims and in the process vied with each other to acquire power and position. Of 968 delegates attending the sixth annual conference of the Hindu Mahasabha in Varanasi in August 1923, 56.7 came from the U.P. The United Provinces (UP), the Punjab, Delhi and Bihar together contributed 86.8 % of the delegates. Madras, Bombay and Bengal combined sent only 6.6% of the delegates. 1920s was a trying period for the Congress. This time the communal tension in the United Province was not only due to the zeal of Hindu and Muslim religious leaders, but was fuelled by the political rivalries of the Swarajists and Liberals.

In Allahabad, Motilal Nehru and Madan Mohan Malaviya confronted each other. When Nehru’s faction emerged victorious in the municipal elections of 1923, Malaviya’s faction began to exploit religious passions. The District Magistrate Crosthwaite who conducted the investigation reported: ‘The Malavia family have deliberately stirred up the Hindus and this has reacted on the Muslims.’

(b) The Hindu Mahasabha

In the Punjab communalism as a powerful movement had set in completely. In 1924 Lala Lajpat Rai openly advocated the partition of the Punjab into Hindu and Muslim Provinces. The Hindu Mahasabha, represented the forces of Hindu revivalism in the political domain, raised the slogan of ‘Akhand Hindustan’ against the Muslim League’s demand of separate electorates for Muslims. Ever since its inception, the Mahasabha’s role in the freedom struggle has been rather controversial. While not supportive of British rule, the Mahasabha did not offer its full support to the nationalist movement either.

Since the Indian National Congress had to mobilize the support of all classes and communities against foreign domination, the leaders of different communities could not press for principle of secularism firmly for the fear of losing the support of religious-minded groups. The Congress under the leadership of Gandhi held a number of unity conferences during this period, but to no avail.

(c) Delhi Conference of Muslims and their Proposals

One great outcome of the efforts at unity, however, was an offer by the Conference of Muslims, which met at Delhi on March 20, 1927 to give up separate electorates if four proposals were accepted. 1. the separation of Sind from Bombay 2. Reforms for the Frontier and Baluchistan 3. Representation by population in the Punjab and Bengal and 4. Thirty-three per cent seats for the Muslims in the Central Legislature.

Motilal Nehru and S. Srinvasan persuaded the All India Congress Committee to accept the Delhi proposals formulated by the Conference of the Muslims. But communalism had struck such deep roots that the initiative fell through. Gandhi commented that the Hindu-Muslim issue had passed out of human hands. Instead of seizing the opportunity to resolve the tangle, the Congress chose to drag its feet by appointing two committees, one to find out whether it was financially feasible to separate Sind from Bombay and the other to examine proportional representation as a means of safeguarding Muslim majorities. Jinnah who had taken the initiative to narrow down the breach between the two, and had been hailed the ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity by Sarojini, felt let down as the Hindu Mahasabha members present at the All Parties Convention held in Calcutta in 1928 rejected all amendments and destroyed any possibility of unity. Thereafter, most of the Muslims were convinced that they would get a better deal from Government rather than from the Congress.

Expressing anguish over the development of sectarian nationalism, Gandhi wrote, ‘There are as many religions as there are individuals, but those who are conscious of the spirit of the nationality do not interfere with one another’s religion. If Hindus believe that India should be peopled only by Hindus, they are living in a dream land. The Hindus, the Sikhs, the Muhammedans, the Parsis and the Christians who have made their country are fellow countrymen and they will have to live in unity if only for their interest. In no part of the world are one nationality and one religion synonymous terms nor has it ever been so in India.’

(d) Communal Award and its Aftermath

The British Government was consistent in promoting communalism. Even the delegates for the second Round Table Conference were chosen on the basis of their communal bearings. After the failure of the Round Table Conferences, the British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald announced the Communal Award which further vitiated the political climate.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (R.S.S.) founded in 1925 was expanding and its volunteers had shot upto 1,00,000. K.B. Hedgewar, V.D. Savarkar and M.S. Golwalker were Hindu Rashtra and openly advocated that ‘the non-Hindu people in Hindustan must adopt the Hindu culture and language… they must cease to be foreigners or may stay in the country wholly subordinated to the Hindu Nation claiming nothing.’ V.D. Savarkar asserted that ‘We Hindus are a Nation by ourselves’. Though the Congress had forbidden its members from joining the Mahasabha or the R.S.S. as early as 1934, it was only in December 1938 that the Congress Working Committee declared Mahasabha membership to be a disqualification for remaining in the Congress.

First Congress Ministries

The nationalism of the Indian National Congress was personified by Mahatma Gandhi, who rejected the narrow nationalism exemplified by the Arya Samaj and the Aligargh movement and strove to evolve a political identity that transcended the different religions. Notwithstanding the state-supported communalism of different hues, the Indian National Congress remained a dominant political force in India. In the 1937 elections, Congress won in seven of the eleven provinces and formed the largest party in three others. The Muslim League’s performance was dismal. It succeeded in winning only 4.8 per cent of the Muslim votes. The Congress had emerged as a mass secular party. Yet the Government branded it a Hindu organisation and projected the Muslim League as the real representative of the Muslims and treated it on a par with the Congress.

Observation of Day of Deliverance

The Second World War broke out in 1939 and the Viceroy of India Linlithgow immediately announced that India was also at war. Since the declaration was made without any consultation with the Congress, it was greatly resented by it. The Congress Working Committee decided that all Congress ministries in the provinces would resign. After the resignation of Congress ministries, the provincial governors suspended the legislatures and took charge of the provincial administration.

The Muslim League celebrated the end of Congress rule as a day of deliverance on 22 December 1939. On that day, the League passed resolutions in various places against Congress for its alleged atrocities against Muslims. The demonstration of Nationalist Muslims was dubbed as anti-Islamic and denigrated. It was in this atmosphere that the League passed its resolution on 26 March 1940 in Lahore demanding a separate nation for Muslims.

Neither Jinnah nor Nawab Zafrullah Khan then had considered creation of separate state for Muslims practicable. However, on March 23, 1940, the Muslim League formally adopted the idea by passing a resolution. The text of the resolution ran as under: “Resolved that it is the concerted view of this session of the All India Muslim League that no constitutional scheme would be workable in this country or acceptable to Muslims unless it is designed on the following basic principles, viz. that geographically contiguous units are demarcated into regions which should be constituted with such territorial readjustments as may be necessary, that the area in which the Muslims are numerically in majority should be grouped to constitute Independent State.” The League resolved that the British government before leaving India should effect the partition of the country into Indian union and Pakistan.

Though the idea of Pakistan came from the Muslim League platform in 1940 it had been conceived ten years earlier by the poet–scholar Mohammad Iqbal. At the League’s annual conference at Allahabad (1930), Iqbal expressed his wish to see a consolidated North-west Indian Muslim State. It was then articulated forcefully by Rahmat Ali, a Cambridge student. The basis of League’s demand was its “Two Nation Theory” which first came from Sir Wazir Hasan in his presidential address at Bombay session of League in 1937. He said, “the Hindus and Mussalmans inhabiting this vast continent are not two communities but should be considered two nations in many respects.”

Direct Action Day

Hindu communalism and Muslim communalism fed on each other throughout the early 1940s. Muslim League openly boycotted the Quit India movement of 1942. In the elections held in 1946 to the Constituent Assembly, Muslim League won all 30 seats reserved for Muslims in the Central Legislative Assembly and most of the reserved provincial seats as well. The Congress Party was successful in gathering most of the general electorate seats, but it could no longer effectively insist that it spoke for the entire population of British India.

In 1946 Secretary of State Pethick-Lawrence led a three-member Cabinet Mission to New Delhi with the hope of resolving the Congress–Muslim League deadlock and, thus, of transferring British power to a single Indian administration. Cripps was primarily responsible for drafting the Cabinet Mission Plan. The plan proposed a three-tier federation for India, integrated by a central government in Delhi, which would be limited to handling foreign affairs, communications, defence, and only those finances required to take care of union matters. The subcontinent was to be divided into three major groups of provinces: Group A, to include the Hindu-majority provinces of the Bombay Presidency, Madras Presidency, the United Provinces, Bihar, Orissa, and the Central Provinces; Group B, to contain the Muslim-majority provinces of the Punjab, Sind, the North-West Frontier, and Baluchistan; and Group C, to include the Muslim-majority Bengal and the Hindu-majority Assam. The group governments were to be autonomous in everything excepting in matters reserved to the centre. The princely states within each group were to be integrated later into their neighbouring provinces. Local provincial governments were to have the choice of opting out of the group in which they found themselves, should a majority of their people desire to do so.

Jinnah accepted the Cabinet Mission’s proposal, as did the Congress leaders. But after several weeks of behind-the-scene negotiations, on July 29, 1946, the Muslim League adopted a resolution rejecting the Cabinet Mission Plan and called upon the Muslims throughout India to observe a ‘Direct Action Day’ in protest on August 16. The rioting and killing that took place for four days in Calcutta led to a terrible violence resulting in thousands of deaths. Gandhi who was until then resisting any effort to vivisect the country had to accede to the demand of the Muslim League for creation of Pakistan.

Mountbatten who succeeded Wavell came to India as Viceroy to effect the partition plan and transfer of power.