Introduction

The influence of the Left-wing in the Indian National Congress and consequently on the struggle for independence was felt in a significant manner from the late 1920s. The Communist Party of India (CPI) was formed, by M.N. Roy, Abani Mukherji, M.P.T. Acharya, Mohammad Ali and Mohammad Shafiq, in Tashkent, Uzbekistan then in the Soviet Union in October 1920. This opened a new radical era in the anti-imperialist struggles in India.

Even though there were many radical groups functioning in India earlier the presence of a Communist state in the form of USSR greatly alarmed the British in India. The first batch of radicals reached Peshawar on 3 June 1921. They were arrested immediately under the charges of being Bolshevik (Russian communist agents) comeing to India to create troubles. A series of five conspiracy cases were instituted against them between the years 1922 and 1927. The first of these was the Peshawar Conspiracy case. This was followed by the Kanpur (Bolshevik) Conspiracy case in (1924) and the most famous, the Meerut Conspiracy case (1929). Meanwhile, the CPI was formally founded on Indian soil in 1925 in Bombay.

Various revolutionary groups were functioning then in British India, adopting socialist ideas but were not communist parties. Two revolutionaries – Bhagat Singh of the Hindustan Revolutionary Socialist Association and Kalpana Dutt of the Indian Republican Army that organised repeated raids on the Chittagong Armoury in Bengal will be the focus of the next section. The Karachi Session of the INC and its famous resolutions especially on Fundamental Rights and Duties is dealt with next. The last two topics are about the world -wide economic depression popularly known as Great Depression and its impact on India and Tamil Society and the Industrial Development registered in India in its aftermath. The Great Depression dealt a severe blow to the labour force and peasants and consequently influenced the struggle for independence in a significant way.

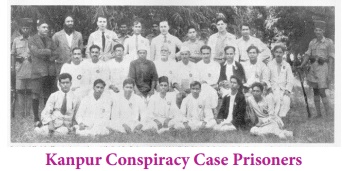

Kanpur Conspiracy Case, 1924

The colonial administrators did not take the spread of communist ideas lightly. Radicalism spread across the British Provinces – Bombay, Calcutta and Madras – and industrial centres like Kanpur in United Province (UP) and cities like Lahore where factories had come up quite early. As a result, trade unions emerged in the jute and cotton textile industries, the railway companies across the country and among workers in the various municipal bodies. In order to curb the radicalisation of politics, especially to check what was then called Bolshevism, repressive measures were adopted by the British administration. The Kanpur Conspiracy case of 1924 was one such move. Those charged with the conspiracy were communists and trade unionists.

The accused were arrested spread over a period of six months. Eight of them were charged under Section 121-A of the Indian Penal Code – ‘to deprive the King Emperor of his sovereignty of British India, by complete separation of India from imperialistic Britain by a violent revolution’, and sent to various jails. The case came before Sessions Judge H.E. Holmes who had earned notoriety while serving as Sessions Judge of Gorakhpur for awarding death sentence to 172 peasants for their involvement in the Chauri Chaura case.

In the Kanpur Conspiracy case, Muzaffar Ahmed, Shaukat Usmani, Nalini Gupta and S. A. Dange were sent to jail, for four years of rigorous imprisonment. The trial and the imprisonment, meanwhile, led to some awareness about the communist activities in India. A Communist Defence Committee was formed in British India to raise funds and engage lawyers for the defence of the accused. Apart from these, the native press in India reported the court proceedings extensively.

The trial in the conspiracy case and the imprisonment of some of the leaders, rather than kill the spirit of the radicals gave a fillip to communist activities. In December 1925, a Communist Conference of different communist groups, from all over India, was held. Singaravelar from Tamil Nadu took part in this conference. It was from there that the Communist Party of India was established, formally, with Bombay as its Headquarters.

13 persons were originally accused in the Kanpur case: M.N. Roy, (2) Muzaffar Ahmad, (3) Shaukat Usmani, (4) Ghulam Hussain, (5) S.A. Dange, (6) M. Singaravelar, R.L. Sharma, (8) Nalini Gupta, Shamuddin Hassan, (10) M.R.S Velayudhun, (11) Doctor Manilal, Sampurnananda, (13) Satyabhakta. 8 persons were charge-sheeted: M.N. Roy, Muzaffar Ahmad, S.A. Dange, Nalini Gupta, Ghulam Hussain, Singaravelar, Shaukat Usmani, and R.L. Sharma. Ghulam Hussain turned an approver. M.N. Roy and R.L. Sharma were charged in absentia as they were in Germany and Pondicherry (a French Territory) respectively. Singaravelar was released on bail due to his ill health. Finally the list got reduced to four.

M. Singaravelar (18 February 1860 – 11 February 1946), was born in Madras. He was an early Buddhist, and like many other communist leaders, he was also associated with Indian National Congress initially. However, after sometime he chose a radical path. Along with Thiru. V. Kalyanasundaram, he organised many trade unions in South India. On 1 May 1923, he organised the first ever celebration of May Day in the country. He was one of the main organisers of the strike in South Indian Railways (Golden Rock, Tiruchirappalli) in 1928 and was prosecuted for that.

Meerut Conspiracy Case, 1929

Communist Activities

The Meerut Conspiracy Case of 1929, was, perhaps, the most famous of all the communist conspiracy cases instituted by the British Government. The late 1920s witnessed a number of labour upsurges and this period of unrest extended into the decade of the Great Depression (1929–1939). Trade unionism spread over to many urban centres and organised labour strikes. The communists played a prominent role in organising the working class throughout this period. The Kharagpur Railway workshop strikes in February and September 1927, the Liluah Rail workshop strike between January and July 1928, the Calcutta scavengers’ strike in 1928, the several strikes in the jute mills in Bengal during July-August 1929, the strike at the Golden Rock workshop of the South Indian Railway, Tiruchirappalli, in July 1928, the textile workers’ strike in Bombay in April 1928 are some of the strikes that deserve mention.

Government Repression

Alarmed by this wave of strikes and the spread of communist activities, the British Government brought two draconian Acts – the Trade Disputes Act, 1928 and the Public Safety Bill, 1928. These Acts armed the government with powers to curtail civil liberties in general and suppress the trade union activities in particular. The government was worried about the strong communist influence among the workers and peasants.

Determined to wipe out the radical movement, the government resorted to several repressive measures. They arrested 32 leading activists of the Communist Party, from different parts of British India like Bombay, Calcutta, Punjab, Poona and United Provinces. Most of them were trade union activists though not all of them were members of the Communist Party of India. At least eight of them belonged to the Indian National Congress. The arrested also included three British communists-Philip Spratt, Ban Bradley and Lester Hutchinson – who had been sent by the Communist Party of Great Britain to help build the party in India. Like those arrested in the Kanpur Conspiracy Case they were charged under Section 121A of the Indian Penal Code. All the 32 leaders arrested were brought to Meerut (in United Province then) and jailed. A good deal of documents that the colonial administration described as ‘subversive material,’ like books, letters, and pamphlets were seized and produced as evidence against the accused.

The British government conceived of conducting the trial in Meerut (and not, for instance in Bombay from where a large chunk of the accused hailed) so that they could get away with the obligations of a jury trial. They feared a jury trial could create sympathy for the accused.

Trial and Punishment

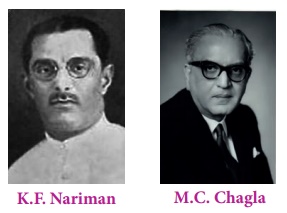

Meanwhile, a National Meerut Prisoners’ Defence Committee was formed to coordinate defence in the case. Famous Indian lawyers like K.F. Nariman and M.C. Chagla appeared in the court on behalf of the accused. Even national leaders like Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru visited the accused in jail. All these show the importance of the case in the history of our freedom struggle.

The Sessions Court in Meerut awarded stringent sentences on 16 January 1933, four years after the arrests in 1929. 27 were convicted and sentenced to various duration of transportation. During the trial, the Communists made use of their defence as a platform for propaganda by making political statements. These were reported widely in the newspapers and thus lakhs of people came to know about the communist ideology and the communist activities in India. There were agitations against the conviction. That three British nationals were also accused in the case, the case became known internationally too. Most importantly, even Romain Rolland and Albert Einstein raised their voice in support of the convicted.

Under the national and international pressure, on appeal, the sentences were considerably reduced in July 1933.

Bhagat Singh and Kalpana Dutt

Bhagat Singh’s Background

Bhagat Singh represented a distinct strand of nationalism. His radical strand complemented, in a unique way, to the overall ideals of the freedom movement.

“I began to study. My previous faith and convictions underwent a remarkable modification. The romance of the violent methods alone which was so prominent among our predecessors was replaced by serious ideas. No more mysticism, no more blind faith. Realism became our cult. Use of force justifiable when resorted to as a matter of terrible necessity: non-violence as a policy indispensable for all mass movements. So much about methods. The most important thing was the clear conception of the ideal for which we were to fight….. from Bhagat Singh’s “Why I am an Atheist”.

Bhagat Singh was born to Kishan Singh (father) and Vidyavati Kaur (mother) on 28 September 1907 in Jaranwala, Lyallpur district, Punjab, now a part of Pakistan. His father was a liberal and his family was a family of freedom fighters. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre happened when Bhagat Singh was 14 years. Early in his youth, he was associated with the Naujawan Bharat Sabha and the Hindustan Republican Association. The latter organisation was founded by Sachin Sanyal and Jogesh Chatterji. It was reorganised subsequently in September 1928 as the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (H.S.R.A) by Bhagat Singh and his comrades. Socialist ideals and the October Revolution in Russia of 1917 were large influences on these revolutionaries. Bhagat Singh was one of the leaders of the H.S.R.A along with Chandrashekhar Azad, Shivaram Rajguru and Sukhdev Thapar.

Bhagat Singh’s Bomb Throwing

The image that comes to our mind at the very mention of Bhagat Singh’s name is that of the bomb he threw in the Central Legislative Assembly on April 8, 1929. The bombs did not kill anybody. It was intended as a demonstrative action, an act of protest against the draconian laws of the British. They chose the day on which the Trade Disputes Bill, an anti-labour legislation was introduced in the assembly.

Lahore Conspiracy Case

Bhagat Singh along with Rajguru, Sukhdev, Jatindra Nath Das and 21 others were arrested and tried for the murder of Saunders (the case was known as the Second Lahore Conspiracy Case). Jatindra Nath Das died in the jail after 64 days of hunger strike against the discriminatory practices and poor conditions in jail. The verdict in the bomb throwing case had been suspended until the trial of Lahore Conspiracy trials was over. It was in this case that Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were sentenced to death on 7 October 1930.

A letter from them to the Governor of Punjab shows their courage and their optimism over the future of India even while facing death for the cause of freedom of their country. It says, ‘the days of capitalism and imperialism are numbered. The war neither began with us nor is going to end with our lives… According to the verdict of your court we had waged a war and we are therefore war prisoners. And we claim to be treated as such i.e., we claim to be shot dead instead of being hanged.”

Some narratives describe Bhagat Singh and his fellow patriots as terrorists. This is a misconception. The legendary Bhagat Singh clarified how his group is different from the terrorists. He said, during his trial, that revolution is not just the cult of bomb and pistol…Revolution is the inalienable right of mankind. Freedom is the imperishable birth-right of all. The labourer is the real sustainer of society.. To the altar of this revolution we have brought our youth as incense, for no sacrifice is too great for so magnificent a cause.’ Symbolically, they also shouted Inquilab Zindabad after this defence statement of his inthe court.

Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were hanged early in the morning of March 23, 1931 in the Lahore Jail. They faced the gallows with courage, shouting Inquilab Zindabad and Down with British Imperialism until their last breath. The history of freedom struggle is incomplete without the revolutionary strand of nationalism and the ultimate sacrifice of these revolutionaries. One more name in the list of such fighters is Kalpana Dutt.

The H.S.R.A was a renewed chapter of the Hindustan Republican Association. Its aim was the overthrow of the capitalist and imperialist government and establish a socialist society through a revolution. The H.S.R.A involved a number of actions such as the murder of Saunders in Lahore. In that, Saunders was mistaken for the Superintendent of Police, Lahore, James A. Scott who was responsible for seriously assaulting Lajpat Rai, in December 1928, and Rai’s subsequent death. They also made an attempt to blow up the train in which Lord Irwin (Governor General and Viceroy of India, 1926-1931) was travelling, in December 1929, and a large number of such actions in Punjab and UP in 1930.

Kalpana Dutt (1913–1995)

In the late 1920s a young woman, Kalpana Dutt (known as Kalpana Joshi after her marriage to the communist leader P.C. Joshi), fired the patriotic imagination of young people by her daring raid of the Chittagong armoury.

To understand the heroism of Kalpana Dutt, you should understand the revolutionary strand of nationalism that attracted women like her to these ideals. You have alreay learnt that there existed many revolutionary groups in British India. The character of these organisations gradually changed from being ones that practiced individual annihilation to organising collective actions aimed at larger changes in the system.

As Surya Sen, the revolutionary leader of Chittagong armoury raid, told Ananda Gupta, ‘a dedicated band of youth must show the path of organised armed struggle in place of individual action. Most of us will have to die in the process but our sacrifice for such noble cause will not go in vain.’ When revolutionary groups like the Yugantar and the Anushilan Samiti began stagnating in the mid- 1920s, new groups sprang out of them. Among them, the most important group was the one led by Surya Sen, a school teacher by profession, in Bengal. He had actively participated in the Non-cooperation movement and wore Khadi. His group was closely working with the Chittagong unit of the Indian National Congress.

Chittagong Armoury Raid

Surya Sen’s revolutionary group, the Indian Republican Army, was named after the Irish Republican Army. They planned a rebellion to occupy Chittagong in a guerrilla-style operation. The Chittagong armouries were raided on the night of 18 April 1930. Simultaneous attacks were launched on telegraph offices, the armoury and the police barracks to cut off all communication networks including the railways to isolate the region. It was aimed at challenging the colonial administration directly.

The revolutionaries hoisted the national flag and symbolically shouted slogans such as Bande Matram and Inquilab Zindabad. The raids and the resistance continued for the next three years. Often, they operated from the villages and the villagers, gave food and shelter to the revolutionaries and suffered greatly at the hands of police for this. Due to the continuous nature of the actions, there was an Armoury Raid Supplementary Trial too. It took three years to arrest Surya Sen, in February 1933, and eleven months before he was sent to the gallows on 12 January 1934. Kalpana Dutt was among those who participated in the raids.

On 13 June 1932 in a face- to-face battle against government forces, two of the absconders of the Armoury Raid were killed, while they in turn killed Capt. Cameron, Commander of the government forces in the village of Dhalghat in the house of a poor Brahmin widow, Savitri Debi. After the incident the widow was arrested together with her children. Despite many offers and temptations, not a word could the police get out of the widow. They were uneducated and poor, yet they resisted all the temptation offers of gold and unflinchingly could bear all the tortures that were inflicted upon them.

—From Kalpana Dutt’s autobiography Chittagong Armoury Raiders’ Reminiscences.

Women in Action

While Bhagat Singh represented young men who dedicated their lives to the freedom of the country, Kalpana Dutt represented the young women who defied the existing patriarchal set up and took to arms for the liberation of their motherland. Not only did they act as messengers (as elsewhere) but they also participated in direct actions, fought along with men, carrying guns.

Kalpana Dutt’s active participation in the revolutionary Chittagong movement led to her arrest. Tried along with Surya Sen, Kalpana was sentenced to transportation for life. The charge was “waging war against the King Emperor.” As all their activities started with the raid on the Armoury, the trial came to be known as the Chittagong Armoury Raid Trial.

Kalpana Dutt recalls in her book Chittagong Armoury Raiders Reminiscences therevolutionary youth of Chittagong wanted “to inspire self-confidence by demonstrating that even without outside help it was possible to fight the Government.

Karachi Session of the Indian National Congress, 1931

The Indian National Congress, in contrast to the violent actions of revolutionaries, mobilised the masses for non-violent struggles. The Congress under the leadership of Gandhi gave priority to the problems of peasants. In the context of great agrarian distress, deepened by world-wide economic depression, the Congress mobilised the peasantry. The Congress adopted a no-rent and no-tax campaign as a part of its civil disobedience programme. Under the pressure of Great Depression, socio-economic demands were sharply articulated in its Karachi Session of the Indian National Congress.

The freedom struggle was taking a new shape. Peasants organised themselves into Kisan Sabhas and industrial workers were organized by the trade unions, made their presence felt in a big way in the freedom struggle. The Indian National Congress had become a mass party during the 1930s. The Congress leadership, which was now taking a left turn under Nehru’s leadership, began to talk about an egalitarian society based on social and economic justice.

The Karachi session held in March 1931, presided over by Sardar Valabhbhai Patel, adopted a resolution on Fundamental Rights and Duties and provided an insight into what the economic policy of an independent India. In some ways, it was the manifesto of the Indian National Congress for independent India. These rights and the social and economic programmes were derived from a firm conviction that political freedom and economic freedom were inseparable.

Even a cursory look at the fundamental rights resolution will tell you that all the basic rights that the British denied to the Indians found a prominent place in the Resolution. The colonial government curtailed civil liberties and freedom by passing draconian acts and ordinances. Gandhian ideals and Nehru’s socialist vision also found a place in the list of rights that the Indian National Congress promised to ensure in free India. The existing social relations, especially the caste system and the practice untouchability, were also challenged with a promise to ensure equal access to public places and institutions.

The Fundamental Rights, in fact, found a place in the Part III of the Constitution of India– Fundamental Rights – and some of them went into Part IV, the Directive Principles of the State policy. You will study more on these in unit 13 of the second volume in the discussion on the Constitution of India.

The Great Depression and its Impact on India

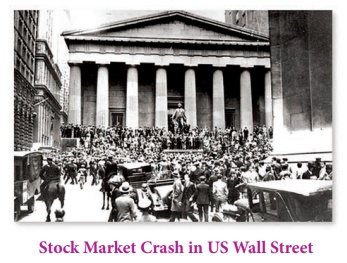

The Great Depression was a severe and prolonged economic crisis which lasted for about a decade from 1929. The slowdown of the economic activities, especially industrial production, led to crises like lockouts, wage cut, unemployment and starvation. It began in North America and affected Europe and all the industrial centres in the world. As the world was integrated by the colonial order in its economic sphere, developments in one part of the world affected other parts as well.

The crash in the Wall Street (where the American Stock Exchange was located) triggered an economic depression of great magnitude. The Depression hit India too. British colonialism aggravated the situation in India. Depression affected both industrial and agrarian sectors. Labour unrest broke out in industrial centres such as Bombay, Calcutta, Kanpur, United Province and Madras against wage cuts, lay-offs and for the betterment of living conditions. In the agriculture sector, prices of the agricultural products, which depended on export markets like jute and raw cotton fell steeply. The depression brought down the value of Indian exports from Rs. 311 crores in 1929–1930 to Rs 132 crores in 1932–33. Therefore, the 1930s witnessed the emergence of the Kisan Sabhas which fought for rent reduction, relief from debt traps and even for the abolition of Zamindari.

The only positive impact was on the Indian industrial sector that could use the availability of land at reduced prices and labour at cheap wage rates. The weakening ties with Britain and other capitalist countries created a condition where growth was recorded in some of the Indian industries. Yet only the industries which fed the local consumption thrived.

Industrial Development in India

The British trade policy took a heavy toll on the indigenous industry. Industrialization of India was not part of British policy. Like other colonies, India was treated as a raw material procurement area and a market for their finished goods.

Despite this, industrial expansion took place in India, because of certain unforeseen circumstances, first during the course of the First World War and then during the Great Depression.

The first Indian to start a cotton mill was Cowasjee Nanabhoy Davar (1815–73), a Parsi, in Bombay in 1854. This was known as the Bombay Spinning and Weaving Company. The city’s leading traders, mostly Parsis, contributed to this endeavour. The American Civil War (1861–65) was a boon to the cotton farmers. But after the Civil War when Britain continued to import cotton from America, Indian cotton cultivators came to grief. But Europeans started textile mills in India, taking advantage of the cheapness of cotton available. Ahmedabad textiles mills were established by Indian entrepreneurs and both Ahmedabad and Bombay became prominent centres of cotton mills. By 1914, there were 129 spinning, weaving and other cotton mills within Bombay presidency. Between 1875–76 and 1913-14, the number of cotton textile mills in India increased from 47 to 271.

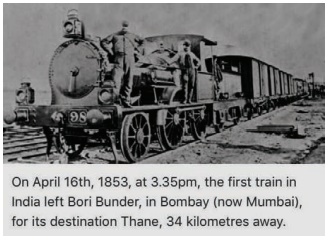

An important landmark in the establishment of industries in India was the expansion of the railways system in India. The first passenger train ran in 1853, connecting Bombay with Thane. By the first decade of the twentieth century, railways was the biggest engineering industry in India. This British-managed industry, run by railway companies, employed 98,723 persons in 1911. The advent of railways and other means of transport and communication facilities helped the development of various industries.

Jute was yet another industry that picked up in India in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The first jute mill in Calcutta was founded in 1855. The growth of jute industry was so rapid and by 1914, there were 64 mills in Calcutta Presidency. However, unlike the Bombay textile industry, these mills were owned by Europeans. Though the industrial development in the nineteenth century was mainly confined to very limited sectors like cotton, jute, etc., efforts were made to diversify the sectors. For example, the Bengal Coal Company was set up in 1843 in Raiganj by Dwarakanath Tagore (1794–1847), grandfather of Rabindranath Tagore. The coal industry picked up after 1892 and its growth peaked during First World War years.

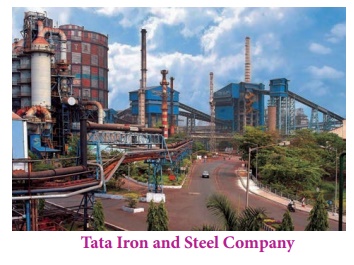

It was in the early twentieth century, industries in India began to diversify. The first major steel industry – Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO) – was set up by the Tatas in 1907 as a part of swadeshi effort in Sakchi, Bihar. Prior to this, a group of Europeans had attempted in 1875 to found the Bengal Iron Company. Following this, the Bengal Iron and Steel Company was set up in 1889. However, TISCO made a huge headway than the other endeavourers in this sector. Its production increased from 31,000 tons in 1912–13 to 1,81,000 tons in 1917–18.

The First World War gave a landmark break to the industrialisation of the country. For the first time, Britain’s strategic position in the East was challenged by Japan. The traditional trade routes were vulnerable to attack. To meet the requirements, development of industries in India became necessary. Hence, Britain loosened its grip and granted some concessions to the Indian capitalists. Comparative relaxation of control by the British government and the expansion of domestic market due to the War, facilitated the process of industrialisation. For the first time, an industrial commission was appointed in 1916. During the war-period, the cotton and jute industries showed much growth. Steel industry was yet another sector marked by substantial growth.

Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, popularly known as J. N. Tata (1839– 1904), came from a Parsi (Zoroastrian) business family in Navsari, Baroda. The first successful Indian entrepreneur, he is called the father of the Indian modern industry. In order to help his father’s business, he travelled all over the world and this exposure helped him in his future endeavours. His trading company, established in 1868, evolved into the Tata Group. A nationalist, he called one of the mills established in Kurla, Bombay “Swadeshi”. His children Dorabji Tata and Ratanji Tata followed his dream and it was Dorabji Tata who finally realised the long term dream of his father to establish an iron and steel company in 1907. His enthusiasm was such that he spent two years in US to learn from the American Iron Industrialists. His yet another dream to set up a hydroelectric company did not materialize during his life time. However, the first major Hydroelectric project – Tata Hydroelectric Company–was set up in 1910. With great foresight the Tatas founded the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

Other industries showing progress were paper, chemicals, cement, fertilisers, tanning, etc. The first Indian owned paper mill – Couper Paper Mill – was set up in 1882 in Lucknow.

Following this, Itaghur Paper Mill and Bengal Paper Mill, both owned by Europeans, were established. Cement manufacturing began in 1904 in Madras with the establishment of South Indian Industries Ltd. Tanning industry began in the late nineteenth century and a government leather factory was set up in 1860 in Kanpur. The first Indian-owned National Tannery was established in 1905 in Calcutta. The gold mining in Kolar also started in the late nineteenth century in the Kolar mining field, Mysore.

The inter-war period registered growth in manufacturing industries. Interestingly the growth rate was far better than Britain and even better than the world average. After a short slug in 1923–24, the output of textile industry began to pick up. During the interwar period, the number of looms and spindles increased considerably.

In 1929–30, 44 per cent of the total amount of cotton piece goods consumed in India came from outside, but by 1933–34, after the Great Depression, the proportion had fallen to 20.5 percent. Other two industries which registered impressive growth were sugar and cement. The Interwar years saw a growth in the shipping industry too. The Scindia Steam Navigation Company Limited (1919) was the pioneer. In 1939, they even took over the Bombay Steam Navigation Company Ltd., a British concern. Eight Indian concerns were operational in this sector. A new phase of production began with the Second World War, which led to the extension of manufacturing industries to machineries, aircrafts, locomotives, and so on

Industrial Development in Tamilnadu during the Depression

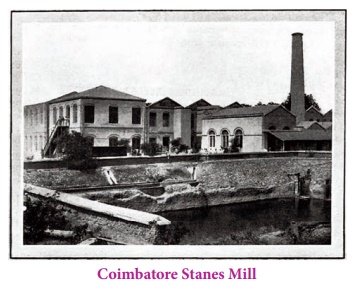

The industrial growth in the Madras Presidency was substantial. In Coimbatore, after Stanes Mill (Coimbatore Spinning and Weaving Mills) was established in 1896, no other mill could come up. The objective conditions created by the Depression like fall in prices of land, cheapness of labour and low interest rates led to the expansion of textile industry in Coimbatore. Twenty nine mills and ginning factories were floated in the Coimbatore area during 1929-37. A cement factory started at Madukkarai in Coimbatore district in 1932 gave fillip to the cement industry in the state. The number of sugar factories in the province rose from two to eleven between 1931 and 1936. There were also proliferation of rice mills, oil mills and cinema enterprise during this period.